Not wanting to follow the conventional paths of COPO Camaro ownership that find the rare car huddled in a collector’s garage or racing in NHRA’s tightly controlled Super Stock class, the septuagenarian owner of this 2013 COPO wanted to go outlaw.

Not wanting to follow the conventional paths of COPO Camaro ownership that find the rare car huddled in a collector’s garage or racing in NHRA’s tightly controlled Super Stock class, the septuagenarian owner of this 2013 COPO wanted to go outlaw.

“He’s 70 years old and didn’t want to learn NHRA-style racing at his age,” explains Todd Patterson of Kansas-based Patterson-Elite Performance where the car’s power and chassis upgrades were completed. “He wanted a more exciting outlet. He wanted to go faster.”

The car originally came with a 427 cubic-inch naturally aspirated engine.

“You couldn’t buy a blown COPO that year, so he decided to do it on his own,” recalls Patterson. “He didn’t care about originality.”

The first shop he tried suggested adding a 4.0-liter Whipple supercharger. Problem was, the shop didn’t change out the 14.5:1 pistons or beef up the aluminum block, and within two runs on the track the bearings were knocked out.

The foundation for this project is a 2013 COPO Camaro (shown in the rear) originally built with the 427-inch naturally aspirated engine and a 2-speed transmission. The owner had already upgraded the rollcage to comply with SFI 25.5 standards for the expected ETs lower than 8.50, which is the quickest time the stock cage is certified for. Basically a Funny Car-style hoop cage is built around the driver with 4130 chromoly tubing, and there are additional gussets and bracing where required.

He got disenchanted and put the car in a barn for two years,” says Patterson. “Then he brought the car to us and, again, said he wanted to go faster. We told him about the 350 cubic-inch supercharged engines we built for Factory Showdown racing. He wanted a blown 427 and he also wanted to use the 4.0 Whipple blower because of money already invested.”

There were restrictions, of course, with transforming the COPO Camaro–which is delivered from GM with numerous racing features, such as a fuel cell, hand-built engine and multi-link rear suspension–into an outlaw ready to run in no-rules competition.

We wanted to keep it simple and use off-shelf parts.–Todd Patterson, Patterson-Elite

Small-tire racing is all the rage these days with numerous radial tire races and “no-prep” challenges around the country. And the owner wasn’t opposed to meeting up with locals on a back road to lay down some rubber.

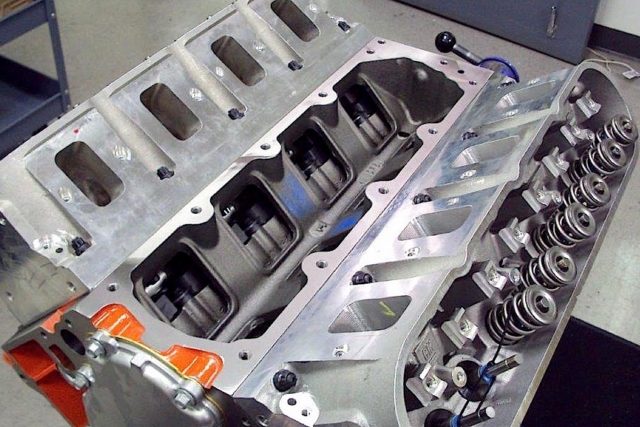

To handle the expected boosted, Patterson-Elite started with an LSX block due to its 6-bolt-per-cylinder pattern to secure the cylinder heads. The block came with a 3.880-inch bore, but for this application it was punched out to 4.120-inch, then diamond-honed to the final 4.125-inch. The block was also line-honed and decked to ensure proper alignment of the internal components before the installation of ARP main studs.

The bottom end starts with a fully counter-weighted Winberg billet crankshaft that features a 4.000-inch stroke and standard-sized bearing journals. The remainder of the rotating assembly comprises 6.125-inch Callies Ultra steel rods and Diamond dished pistons secured with Trend .927-inch, H13 steel wrist pins. The package is completed with Total Seal piston rings (1mm, 1mm, 3mm). Behind the Cloyes timing set is a Bullet hydraulic roller camshaft (250/265 at .050; .650 lift; 115.5-degree LSA) Note the Melling high-volume oil pump.

The aluminum block that came with the LS7 was discarded in favor of an iron LSX block. The new strategy was to build a stout, easy-to-maintain long-block for the Whipple. The LSX block was a sound choice as it offers 6-bolt-per-cylinder head-bolt pattern and a very robust bottom end. Patterson-Elite bored and honed the new block out to 4.125-inch and added ARP main and head studs.

“We wanted a good cylinder block because we were building quite a bit of boost,” adds Patterson.

In gathering parts for the engine, Patterson leveraged past performance builds with numerous COPO Camaro projects.

The GM LSX-LS7 cylinder heads are fit with 2.205-inch titanium intake valves and 1.615-inch sodium-filled exhaust valves. Out of the box they will flow nearly 400 cfm at .700-inch intake valve lift. The engine features modified GM tie-bar style .842-inch hydraulic lifters and Trend 7/16-inch diameter pushrods.

“We wanted to keep it simple and use ‘off-the-shelf’ parts, those that we’re familiar with,” says Patterson. “So that as you cycle parts through the engine you’re not waiting on custom pieces.”

For example, even though Patterson ordered a Winberg billet crankshaft, he kept the bearing dimensions stock.

“That way we could use a standard off-the-shelf rod,” says Patterson.

Finishing off the rotating assembly are Callies steel rods, Diamond dished pistons, Trend wrist pins and Total Seal rings.

The cylinder heads are sealed with Fel-Pro MLS head gaskets. Valvetrain components include PAC springs, retainers and locks. Although not shown, the engine utilizes 1.8:1 GM pedestal-mounted rocker arms. The ATI damper is the same one that comes on a COPO Camaro with the 350ci supercharged engine. Final compression ratio is 9.5:1.

Cam selection was motivated by ease of maintenance.

“We went with a Bullet hydraulic roller because the customer didn’t want to pull the valve covers after every run,” says Patterson. “We do use GM tie-bar-style lifters that we modify heavily to take most of the bleed out so they operate almost like a solid lifter.”

The owner supplied the 4.0-liter Whipple supercharger and intercooler intake manifold. A separate pump, plumbing and trunk-mounted reservoir were set up to feed the intercooler. Patterson-Elite beefed up the supercharger drive with a billet belt tensioner from American Racing Solutions and special Gates belt. Note the stock water pump, as the owner signaled intentions of pursuing street action. Also shown are the MSD coils and plug wires.

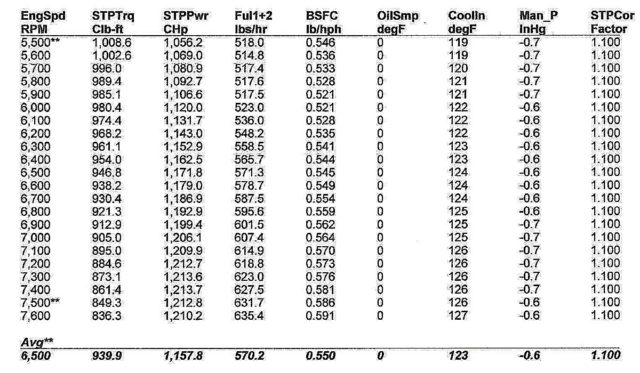

On the dyno the engine pulled over 1,200 horsepower from 7,000 to 7,600 rpm. The engine runs on VP Racing C25 gas and max timing was set at 28 degrees.

The cam is turned by a Cloyes timing set. Budget restraints pointed the team towards the GM LSX-LS7 cylinder head that was fit with PAC retainers, locks and dual springs rated at 700 pounds open.

“The head still uses a pedestal-style rocker, so we didn’t have to put together a shaft system,” adds Patterson.

The chassis was upgraded with PRS-Penske shocks in the rear (middle photo) that required fabricated upper mounts to accommodate the double-Heim arrangement. Note the suspension-travel sensors for the front and rear shocks.

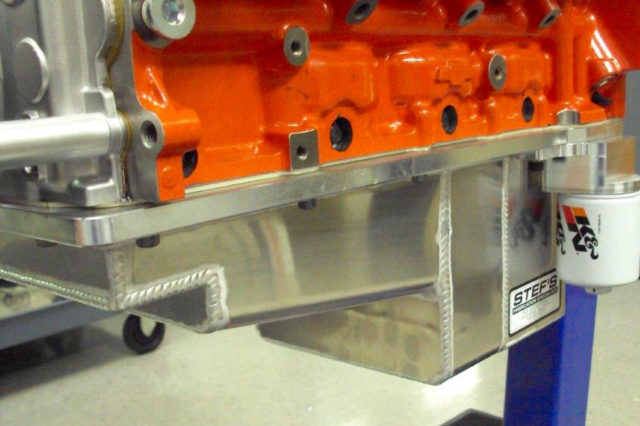

Lubrication was also kept simple, utilizing a stock-style Melling high-volume oil pump and installing a 7-quart Stef’s pan designed to fit the COPO chassis.

“We didn’t go with a dry sump because of cost and packaging concerns,” says Patterson.

The long block was assembled with ARP fasteners, ATI damper and Fel-Pro MLS head gaskets.

“Even with the amount of boost, we felt the MLS gasket would work and we wouldn’t have to O-ring the block and put a receiver groove in the head,” says Patterson.

Patterson-Elite added a Racepak V300 data logger to monitor critical engine, driveline, electrical and suspension functions. The shop also installed a Precision Products shifter with all-forward shifting and an Advanced Control Devices shift control to operate the Coan 3-speed automatic transmission.

The Whipple supercharger comes with an intake manifold and internal intercooler. The belt drive was improved with a billet tensioner from American Racing Solutions and a special Gates ribbed belt. Patterson installed Siemans 80-pound injectors that flow VP Racing C25 gas. Spark is provided by MSD coils. Fuel and ignition are controlled with a Holley HP ECU.

On the dyno the engine topped out at 1,213.7 horsepower at 7,400 rpm, making more than 1,100 horsepower from 5,900 up to the redline at 7,600 RPM. Boost was set at 17 pounds, so there’s potential for more power with a pulley change.

An extra Optima battery was installed to keep plenty of juice flowing to the The engine is Holley HP ECU. Patterson-Elite also upgraded the alternator to a MSD unit to charge the dual setup. The factory COPO fuel cell holds VP Racing C25 gas, and the reservoir for the intercooler is also mounted in the trunk.

Bogart Racing Wheels were modified with bead locks to support the Mickey Thompson tires in the rear. Up front are the stock Hoosier tires on Bogart wheels.

Taking that power to the rear axle is a Reactor flexplate, 10-inch Coan torque converter and Coan 3-speed Big Dog 400 XLT transmission with a 1.77:1 low gear and transbrake. It’s controlled with a Precision Performance Products shifter and an Advanced Control Devices shift control.

The factory rear end also needed some beefing up with a new Strange center section and 40-spline axles.

Most of the chassis modifications follow the Patterson-Elite formula for setting up a COPO to race in the Factory Showdown. PRS-Penske shocks are added in the rear, which require new upper mounts. The Penske shock is a dual-Heim arrangement, so proper brackets have to be fabricated and bolted in place. The shop also installs suspension sensors that are fed into a RacePak data logger. Finally, Lamb brakes were installed at all four corners, and the front bushings were upgraded to help reduce vibration during shutdown.

Final vehicle prep includes installing wheelie bars and a safety parachute.

Attention then turned to tires.

“10.5-inch is all we can get on the stock axle,” says Patterson. “The COPO originally comes with a 9-inch tire on a 10.25-inch wide wheel. We go to an 11-inch wheel but the critical issue is backspacing to get the tire to fit.”

The team uses Mickey Thompson drag radials on beadlocked Bogart wheels. The stock Hoosier skinny tires were relocated to a matching set of Bogart wheels for the front.

As a 427 naturally aspirated car, it’s best time would have been in the 9.70 or 9.60 range.

“It’s already going a full second faster,” confirms Patterson, noting that much of the post-transformation action has been on no-prep, back-country surfaces where conditions for tuning for quick ET isn’t ideal. “He wanted to run in the eights, possibly low eights. He didn’t care about originality.”