With it being so easy to make power these days, getting into the quadruple-digit range isn’t such an amazing feat any longer. However, Dave Adkins has been at the forefront of the competition LS engine market, campaigning a max-effort LS for the past eight years in his Impala–and soon to be an all-new Camaro currently being readied for competition. The Impala has been through various iterations and run in a number of top-tier organizations and classes including–most recently–the NMCA’s Radial Wars class, which is full of stiff competition from some of the best racers in the world.

Paving The Way

Adkins’ journey with the LS is due in part to his racing partner, TJ Grimes, who happens to work at Baker Engineering.

“I was working with TJ Grimes at Baker Engineering on an LS project in my turbocharged GTO, and I really wanted to put [an LS] in my Impala,” Adkins says. That street car project led to what is one of the baddest LS engines ever built.

“This is our fifth generation of LS engine in the past eight years,” says Adkins. “We started off with a Big Stuff3, an LSX block and some cathedral port heads, and went 6.90s at 200 the first year out with the Impala and the twin-88mm turbos. From there, we just kept trying to go faster and faster and get better with the LS engine.”

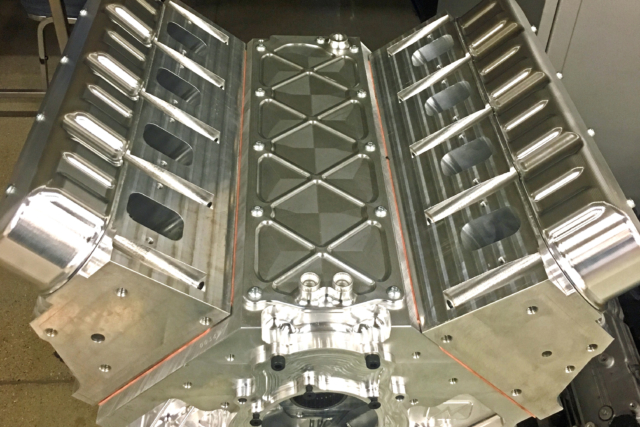

The Noonan billet tall-deck block houses 4.125-inch cylinder bores and a 4.00-inch-stroke billet crankshaft, making for a total of 427 cubic-inches of displacement.

The next evolution of Adkins’ competition engine consisted of a Warhawk block with Chevrolet Performance LSX DR heads. With that combination, we went 6.36 at 223 mph on slicks in the Impala, and that’s when we started cracking cylinder heads,” Adkins says. “We continued to push the parts to the limit and build new parts, and try new parts.”

The third iteration of LS power for Adkins consisted of a Compacted Graphite Iron LSX block, with the first appearance of billet components in the form of Baker Engineering billet cylinder heads. “The Baker LS heads were modeled after the LSX DR heads, so I could run the same intake on the combination,” Adkins says.

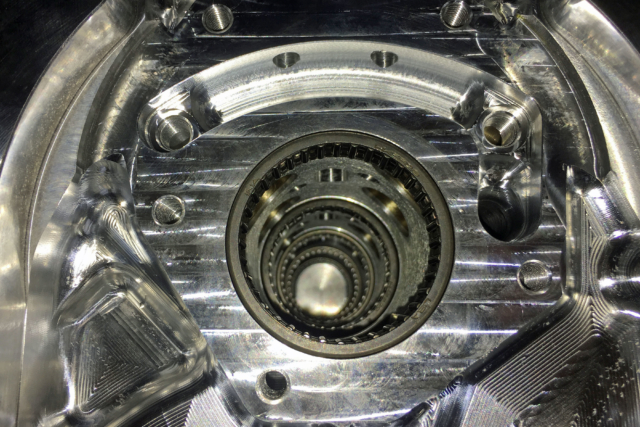

The tall-deck block offers options for a raised cam location, and the ability to use up to 60mm roller cam bearings. Obviously Adkins opted for the roller bearings on both of his max-effort race engines, but in the 55mm variety.

That combination lasted him through almost two seasons of competition before he, once again, found the failure point of the combination. “That engine made 58 passes in 2016 and then lasted 40 passes in 2017 before the block cracked in half. We ripped out all but one main and split it right down the middle,” Adkins says. “It went 4.02 at 191mph right before it let go.”

That failure led to his fourth-generation combination–which was already in the process of being built–saving his racing season.

“We held the points lead for half the season, and the engine let go in Joliet, with two more races left,” says Adkins. “I had already started the new build with a Noonan billet block, and we were waiting on a crank. We scrambled to make the next race in Norwalk with the all-billet engine.”

Adkins’ Thomsen Motorsports billet intake manifold has been an integral part of his program since he was running cast LSX DR heads. Since the Baker Engineering billet heads mimic the LSX DR heads, it was able to be carried over without a problem.

The Billet Beast

Adkins All-Billet beast, as he alluded to, is based around a Baker Engineering tall-deck Billet LS block, punched out to a conservative 4.125-inch bore A 4.00-inch stroke billet steel crankshaft from either Bryant or Winberg (that will make sense a few paragraphs down) makes for 427 cubic-inches of displacement.

Ross custom severe-duty turbo pistons with Total Seal rings are hung of GRP aluminum rods, with Clevite bearings used throughout. Standard camshaft bearings have been replaced by a needle bearing setup, and a Jesel Belt Drive was utilized for the last two races of the season. A custom-fabricated Baker Engineering ProCam oil pan works with the custom Dailey Engineering four-stage belt-driven rotor-pump setup.

Running a custom four-stage dry-sump oil pump setup from Dailey Engineering requires the use of a custom-fabricated Baker Engineering ProCam oil pan.

Topping off the shortblock are a pair of Baker Engineering solid billet inline-valve cylinder heads, based off of the GM LSX DR. The ports have been designed for maximum flow, and measure 430 cfm on the intake side. A 55mm Baker Engineering-spec’d turbo grind camshaft from Brian Tooley Racing inside roller-bearings controls the combination. Isky Racing Cams .937-inch keyway roller lifters ride the cam and move the Trend double-taper one-piece cup style pushrods, which then articulate the Jesel steel shaft rockers at 8,800 rpm.

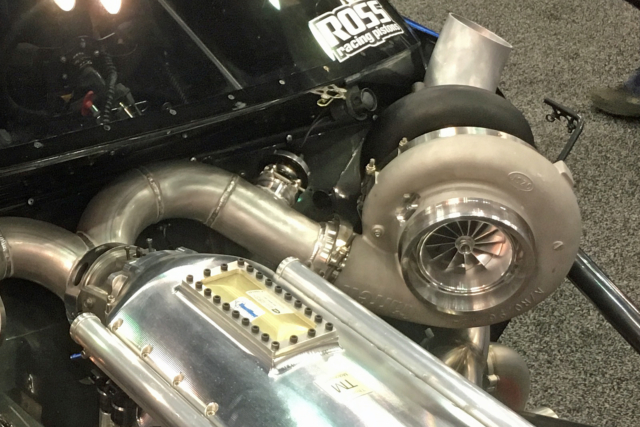

Controlling the fuel is a Holley Dominator EFI system with Billet Atomizer fuel injectors fed by a Waterman mechanical fuel pump, a Wilson billet throttle body feeding a Thomsen Motorsports billet intake manifold. Woolf Aircraft turbo manifolds, built by Baker Engineering feed into the twin Garrett GTX-5533 Gen 2 88mm turbochargers, which combine to make over 60 psi. Turbosmart valves are used to control the boost via dual 60mm ProGate wastegates and dual 50mm Race Port blowoff valves. The ignition is handled by the Holley Dominator, with a coil-near-plug setup.

The Baker Engineering cylinder heads are solid billet pieces which are based on the cast GM LSX DR head. The massive intake ports flow 430 cfm and hold up under 60-plus pounds of boost.

Generation Five

Adkins’ next generation of his LS would probably be more aptly described as generation 4.5, but started as soon as the 2017 racing season ended – with only two events and nine passes on the all-billet combination. “We were in a hurry to get it together, but didn’t take any shortcuts,” Adkins says. “The only changes I’m making right now, to the engine itself, is that everything from this engine will be going into a new block.”

Fortunately, the swap has nothing to do with component failure, but rather a convenience and future-proofing step. “I’m building a second engine for my Camaro (which you can read about here), which will be identical to this one for the Impala,” says Adkins. “I want to go to an RCD gear drive on both of them so that everything is interchangeable between the two. So I’m going to sell the 9-pass block and the Jesel drive, and put everything into a new block.”

Twin Garrett GTX 5533 Gen 2 88mm ball-bearing turbochargers provide the 60-plus pounds of boost to Adkins’ 427 LS engine, while dual Turbosmart wastegates and blow-off valves manage the boost.

In addition to the mechanical changes, Adkins will be switching ignition setups in the off-season looking not only for more power, as heads-up racers are apt to do, but also the associated widening of the tuning window. “We struggled with getting the methanol to run, initially,” says Adkins. “I finally put a mag on the car and everything turned around. Then we switched to the Holley EFI and got away from the mag and went to the smart coil.”

Unfortunately, without the magneto setup, Adkins started having issues above 45 pounds of boost. “At 60 psi the Smart Coil isn’t quite hot enough to give us the AFR we’d like, to keep the engine safe. Basically, we have to have it all perfect, with no margin for error on a pass,” Adkins says. “So we are going to a FTSpark CDI box from Fuel Tech. We’re going to wire that into the Holley, and run eight dumb coils. From what I can see, we’ll have quite a bit more spark energy.”

The Smart Coils are rated at 102 millijoules, which is significantly higher than stock LS coils, but quite a bit less than the output of a racing magneto system. “If you go by the numbers, we’ll be about halfway between the smart coils and a magneto with this new setup,” Adkins says. “Hopefully we’ll be able to get to a safer AFR – we are currently running a brake specific fuel consumption of 1.6 or so [on methanol], but usually, these kinds of combinations are run closer to 2.0 BSFC. With more spark, we can ignite a richer mix, which will be safer, and probably make more power in the process.”

For 2018, Adkins has built not only a new car, but a twin to his 427 all-billet LS engine. With all the same specs and parts, the two engines will be capable of interchanging parts throughout the season, should the need arise.

Will It Break the 3,000 Horsepower Mark?

As we alluded to in the title, based on horsepower calculations, Adkins’ all-billet combination should be north of the 3000-horsepower mark already. “We dyno for testing, not so much for numbers,” Adkins says. “But I can say, on Baker Engineering’s new Dynojet, with a misfire issue, we made 2,250 horsepower to the rear wheels at 42 psi. I’d think, based on trap speed and the weight of the car, it’s close to 3,000 horsepower. That’s just a calculator guess, though. At the end of the day, as long as you’re quicker than the guy next to you, that’s what matters.”

Being faster than the car in the other lane has proven to be a more-often-than-not proposition for Adkins, as he finished 2017 in the third spot in NMCA Radial Wars points, holds the LS eighth-mile world record with a 3.940-second run, with a best trap speed of 192 miles per hour. Weighing in at 2,605 pounds, various calculators gives us between 2,865 and 2,950 horsepower at the tire from the all-billet, twin-turbo, 427 cubic-inch LS-based engine.

Adkins’ list of racing accolades and records is impressive, and is only going to expand with the slightly new engine program in 2018. Based on weight and eighth-mile trap speeds in his Impala, it’s safe to say the engines are making north of 3,000 horsepower.