This article is the second in a series, exploring the “old-school” world of four-barrel carburetors. While some may scoff at this as tantamount to studying the Dead Sea Scrolls or ancient antiquities, the carburetor is far from dead and is in fact doing quite well, thank you. So gaining a little knowledge about the secrets about carburetors might just make you the neighborhood go-to guy.

This episode will deal with the many shades of the Holley four-barrel carburetor. For more than half a century this fuel mixer has been on the scene. It has survived – if not thrived – in part due to its ability to not just flow vast amounts of air and fuel, but also because it is so easy to tune. But before we delve into uncovering its internal tuning secrets, you must first learn how to speak the language.

Language of the Holley

Carburetor size is always on everybody’s mind, so let’s start with airflow ratings. Holley offers likely the widest assortment of sizes of any of the carburetor companies on the market. All of Holley’s models are rated in cubic feet per minute (cfm) with the smallest four-barrel rated at 390 cfm and ending with the Dominator line of racing carbs that now extends to 1,475 cfm. These sizes range through multiple configurations and options. Airflow is determined by the diameter of the venturis (the main body of the carburetor) combined with the diameter of the throttle plates. By mixing main bodies and throttle plates, Holley can offer a tremendously wide selection of carburetor sizes.

Size is likely the first question that most enthusiasts will ask when looking for a carburetor. Holleys are rated in cfm and four-barrel carbs range in size from 390 cfm all the way up to the monster Dominators that can flow up to an astonishing 1,475 cfm. The carb on the left is a Quick Fuel 650 cfm with vacuum secondaries, while the monster on the right is a 1050 cfm Holley Dominator.

While all the Holley carbs being discussed are all four-barrel carbs, they don’t all operate all the same way. The secondary set of throttles can be actuated mechanically with simple linkage or through a vacuum-operated opening that is controlled by a large diaphragm hooked to the secondary throttle linkage. There are advantages and disadvantages to both designs. For street engines the selection is based more on personal preference.

With the incredible selection and different features across the company’s lineup, this is where it can become a little confusing. On the street carburetor side, Holley offers a less expensive version of its four-barrel, dubbed a 4160-style, which is slightly different from the classic 4150 version.

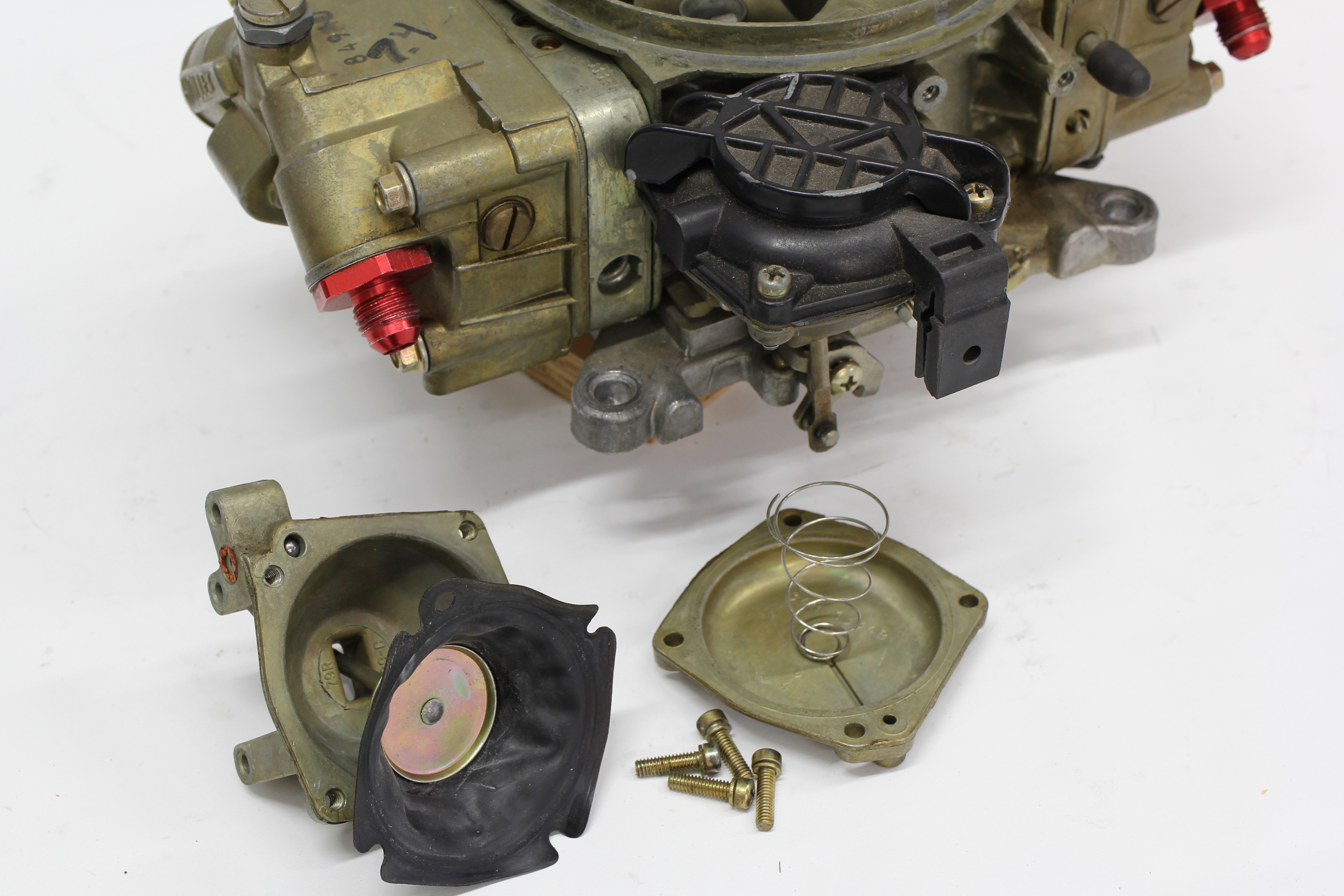

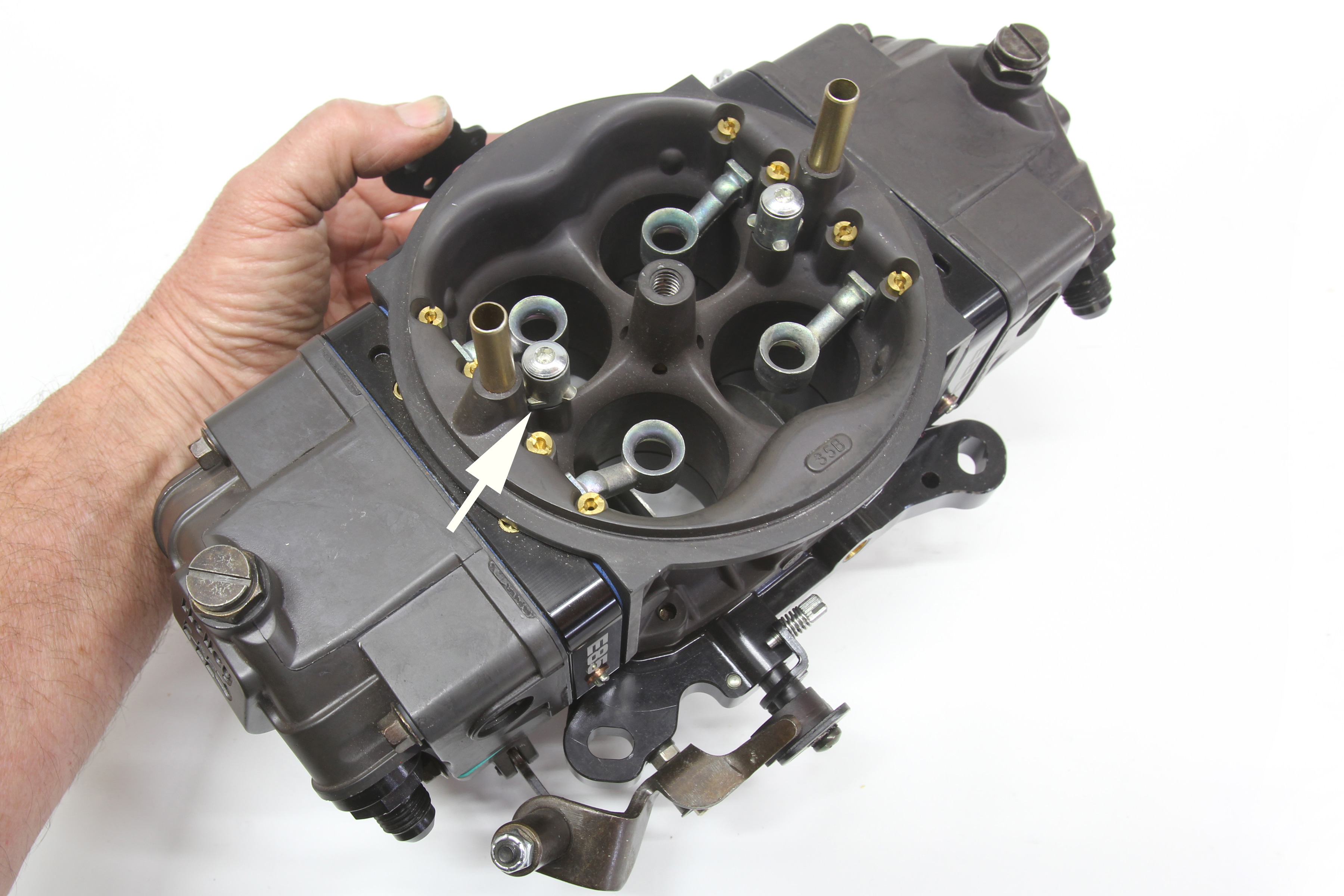

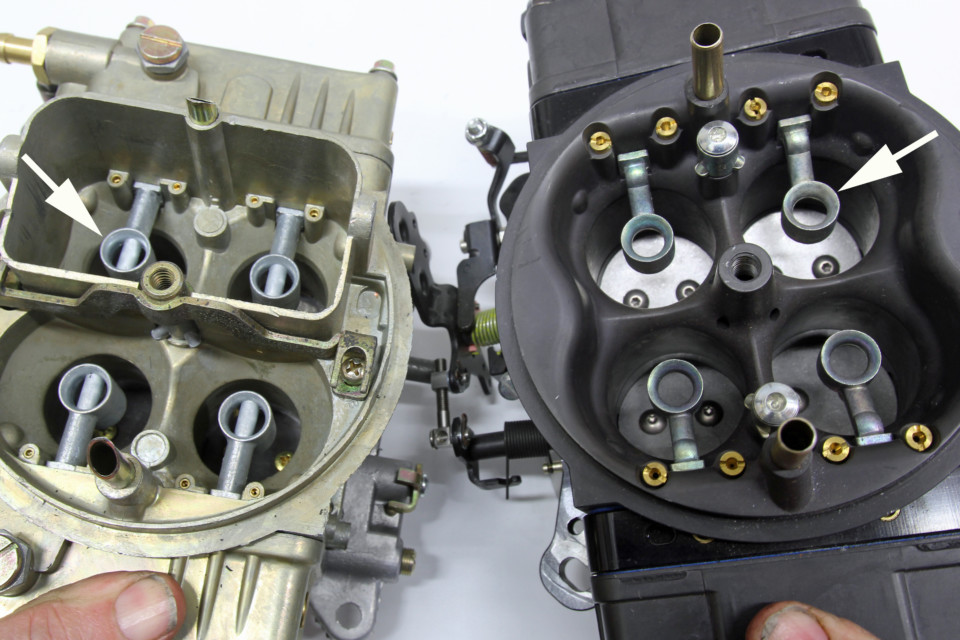

Holleys offer two ways to actuate the secondary throttle bores – either mechanical or vacuum actuation. Vacuum secondary versions (left) employ a diaphragm housing that works against a small spring inside the housing to pull the secondary throttle open. We disassembled the housing so you can see the diaphragm and spring. The housing mounted on the carburetor is a Holley Quick Change piece that makes changing springs very easy. Mechanical secondary linkage is very simple and can be adjusted with optional parts (right). A mechanical secondary carburetor is easily identified by the secondary accelerator pump nozzle located over the secondary venturis (arrow), as vacuum secondary carburetors do not require secondary accelerator pump.

4150 vs. 4160

The 4150 carb employs a metering block on both the primary and secondary side. These metering blocks feature removable jets that can be used to fine-tune the fuel curve, whereas the less expensive 4160 four-barrel version replaces the secondary metering block with what is called a metering plate. This plate bolts directly to the main body of the carburetor and uses a pair of fixed main metering restrictors for jetting.

There really isn’t a performance difference between a 4160 and 4150 carburetor. However, when tuning, it’s much easier to tune secondary metering with jets as opposed to having to remove and replace the secondary metering plate on a 4160 style carburetor.

Different metering plates can be ordered through Holley but if primarily wide-open-throttle (WOT) tuning is anticipated, a secondary metering block with jets is much easier (and less expensive) to tune. One advantage for the 4160 style carb, however, is that a pair of these can be bolted inline on a tunnel ram because of their shorter overall length.

(Left) 4160 style Holleys use a metering plate instead of a metering block. The fuel is metered by a pair of fixed jets located at the bottom of the plate. Holley offers a kit to convert a 4160 to a 4150 style if you choose to upgrade one of these carburetors. (Right) Idle mixture screws on all Holleys are located on the metering blocks. A typical two idle circuit carb will have two screws on the primary metering block. Some performance carbs are equipped with a four idle mixture screws with the additional screws placed in the secondary metering block.

Everything Is Adjustable

One big reason Holleys are so popular with tuners is because they offer such a wide range of tuning opportunities. Idle speed and idle mixture tuning is something that all carburetors offer and most Holleys employ adjustable idle mixture screws on the primary side to accomplish this task. Larger carburetors which are used on more aggressively cammed engines with single-plane manifolds can benefit from idle mixture screws on all four corners instead of just on the primary side.

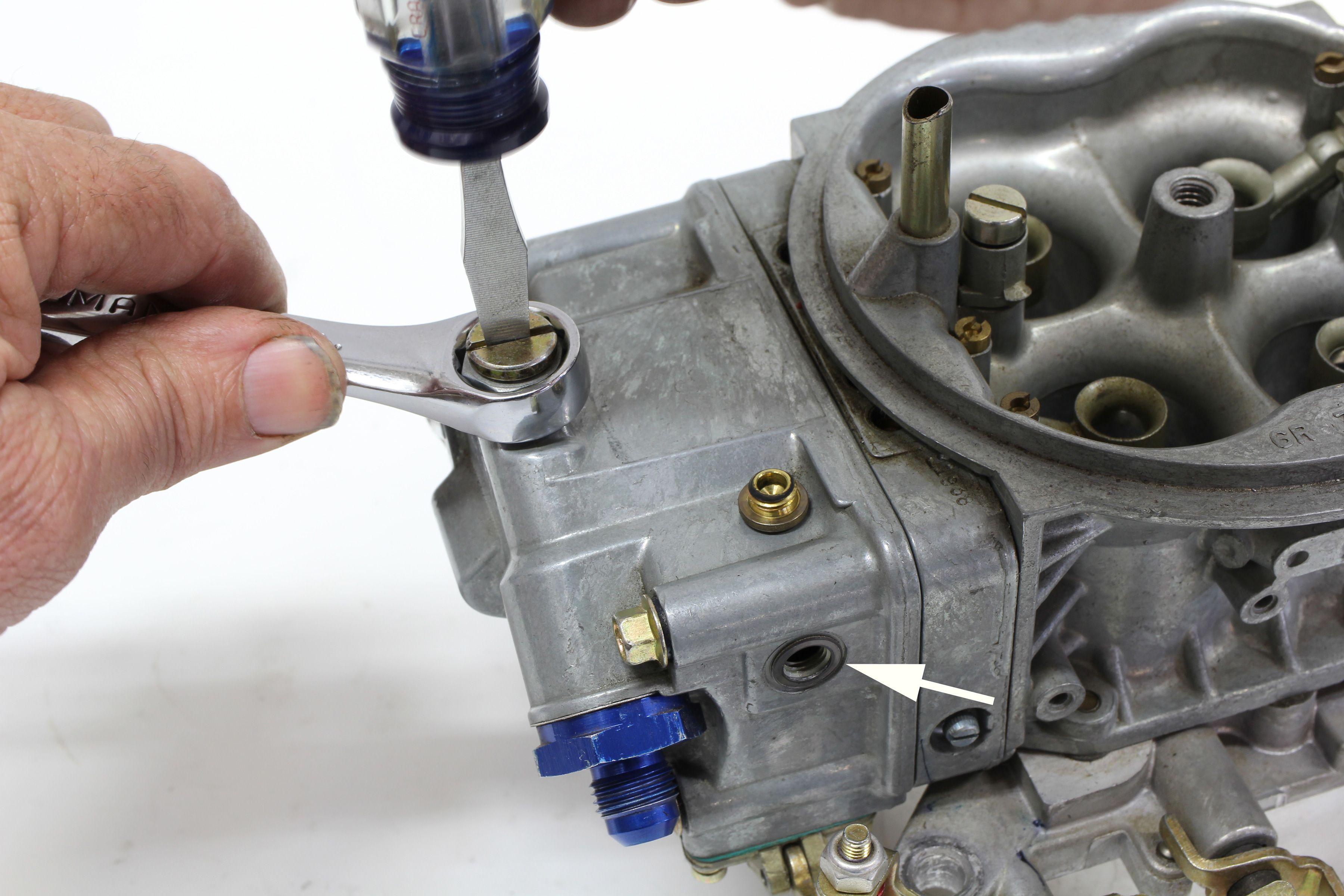

Tuning can also be affected by float level. Most other four-barrel carburetors require disassembly in order to adjust the float. Holley made this change much easier with a simple lock screw and adjustment nut that allows the tuner to modify the float height. Assisting with this, a small, removable plug or a sight window in the side of the float bowl allows easy visual verification of the float level. This is best done with the engine idling.

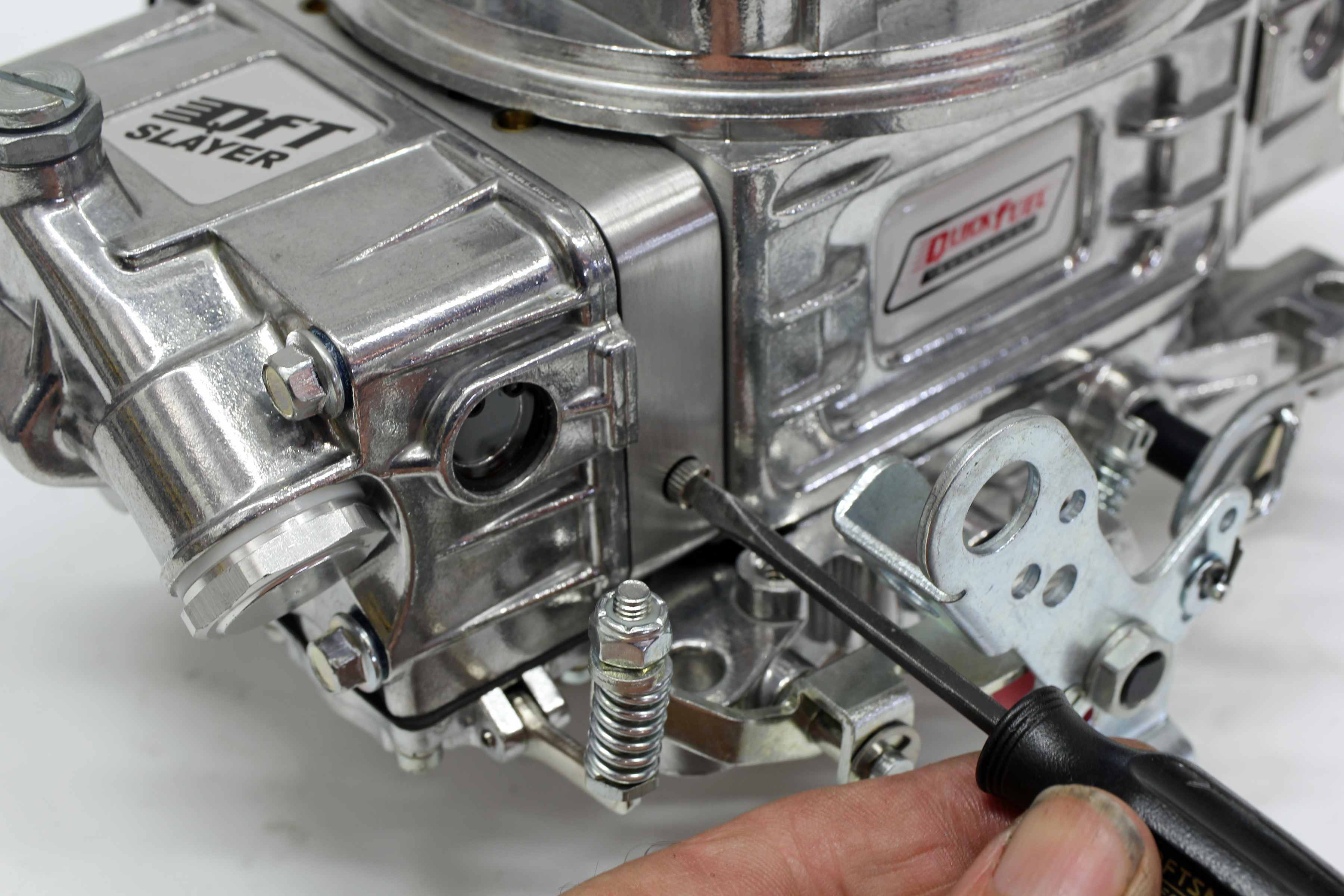

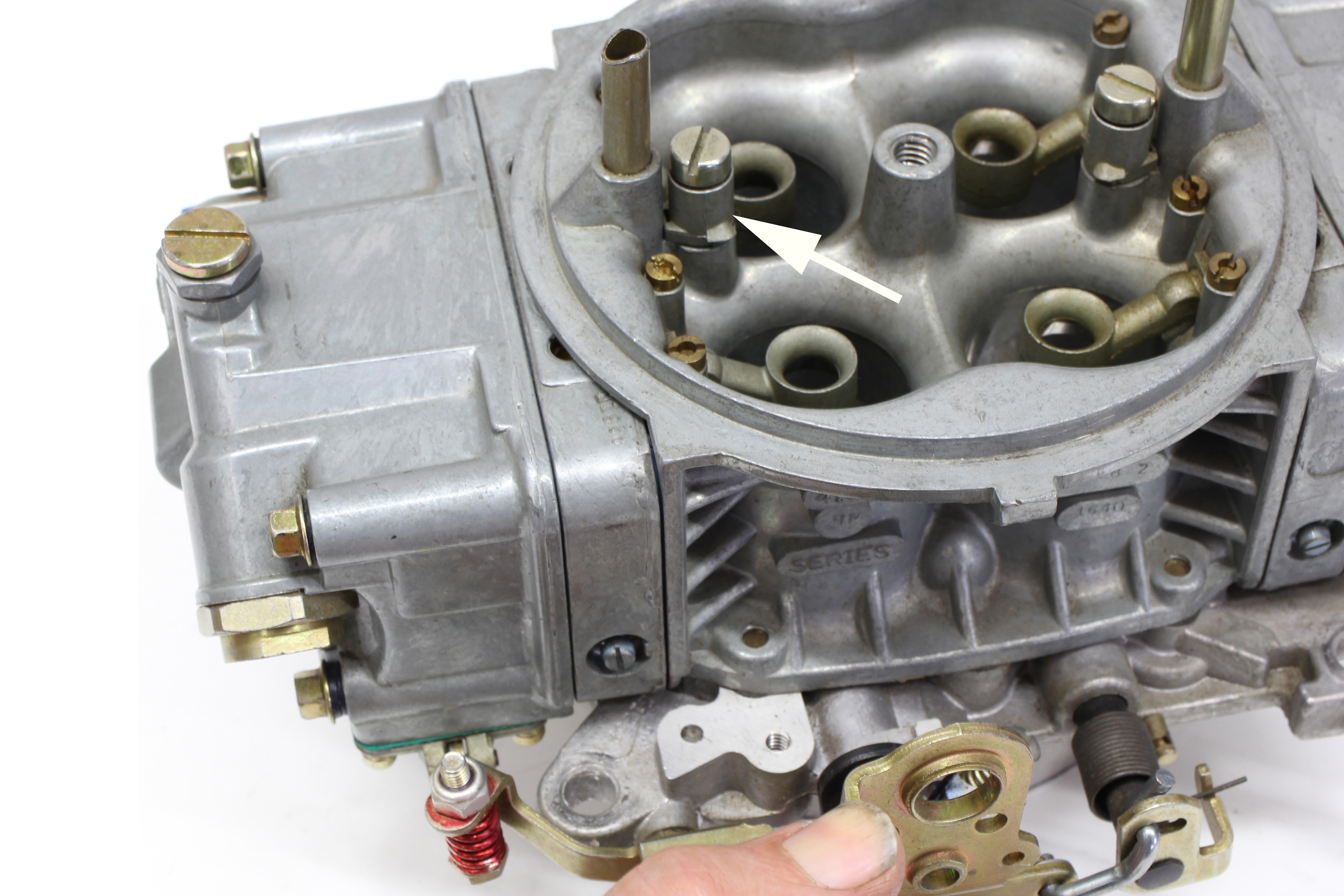

Holleys allow easy adjustment to circuits like the accelerator pump. Even a the most basic Holley with only a primary accelerator pump circuit can be modified with both nozzle size and different pump cams to optimize this circuit. (Left) The arrow points to the accelerator nozzle that discharges the fuel into the venturi. (Right) Holleys also offer float levels that are externally adjustable. To adjust this level, loosen the lock screw and use a 5/8-inch wrench to raise or lower the level. Turning the adjuster nut clockwise lowers the level while counterclockwise raises fuel level. This should be set with the engine running where the fuel is below the bottom of sight plug (arrow).

The modular Holley accelerator pump design also enjoys quite a range of adjustments. This circuit squirts fuel into the primaries (and if the carburetor is a mechanical secondary version, it also injects on the secondary side). This shot of fuel is needed to cover up quick throttle opening at low engine speeds when the air velocity through the carburetor is initially very low. Don’t worry if this sounds complicated, we’ll get into more detail on how to tune this circuit and others in a later installment.

Vacuum secondary carburetors don’t require a secondary accelerator pump circuit because the secondary throttles open only after there is sufficient airflow through the primary side to allow the secondary to open gradually as the engine demands more airflow. This gradual opening means there is sufficient signal for the carburetor to provide the additional fuel needed.

Boosters are the round protrusions in each venturi where fuel is introduced into the air stream. Holley uses several different booster designs. Street-oriented carburetors use a straight style booster (left arrow) while more performance oriented carburetors use a dropped leg booster (right arrow). There are also annular boosters that we will detail in a later story.

Getting Choked Out

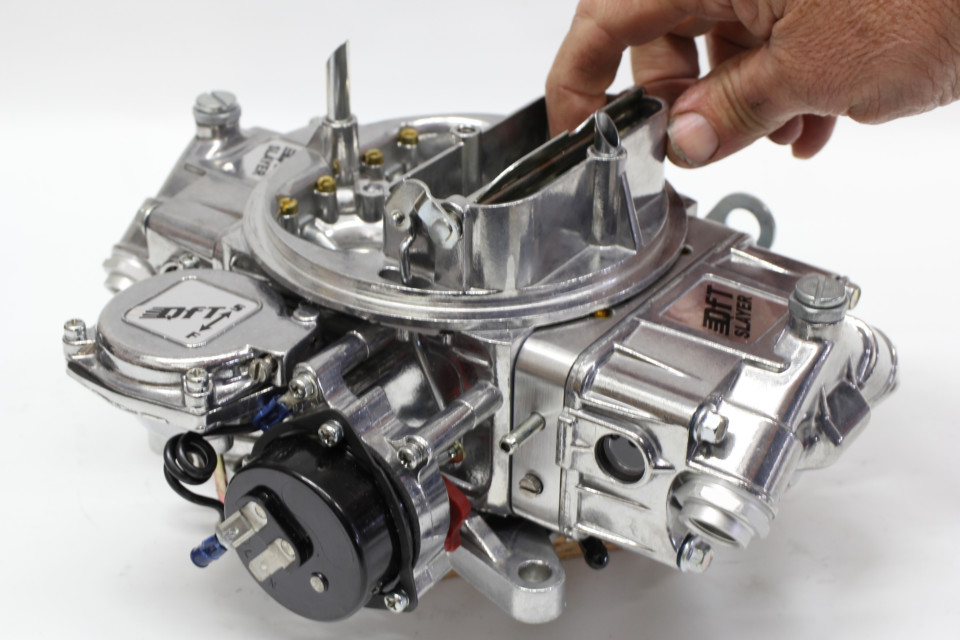

There have been several upgrades to the classic Holley four-barrel configuration over the years. In the past, a classic modification was to remove the choke linkage and mill the choke housing off the carburetor main body to improve airflow. Holley now offers multiple performance carburetor lines – like the HP, Ultra, Dominator and others – that not only eliminate the choke horn out of the box, but offer a nice radius into the venturis.

Other changes include certain models that employ an idle bypass feature. We will get into the details on idle bypass in a future episode of Carb Science but this bypass feature allows properly setting the idle speed throttle blade position on carbureted engines with big camshafts with low vacuum levels at idle.

For street operation, an electric choke system allows the engine to run at fast idle with the choke blade partially closed to create a richer mixture. After the engine warms up, the electric heating element expands a bi-metal spring inside the housing and pulls the choke blade vertical and returns idle speed to the normal curb idle position.

As this series continues, we will dive deeper into the classic Holley carburetor and reveal how to tune and modify these carburetors in order to produce the exact fuel delivery curve necessary for your engine. For a typical street car, these carburetors work exceptionally well and produce a curve that is very close to ideal for most situations.

However, if you are so inclined, digging deeper into the carburetor to custom tune how and when fuel is delivered, will generally result in both a more efficient running engine as well as more power and torque. It’s all a matter of understanding how the circuits work and then how to make them work best for your engine.

We’ve removed the primary metering bowl to reveal the primary metering block. The two primary jets are located near the bottom of the metering block while in between is the power valve. The power valve opens at a predetermined point as the throttle is opened to introduce more fuel into the main metering circuit. This allows the primary side to run leaner jets for part-throttle operation to improve fuel mileage. Once the throttle is fully open, the combination of the jets and the power valve circuit supply the proper amount of fuel so the engine does not run excessively lean