It’s a nice sunny weekend, and you have decided that you and your car are going to spend a Sunday afternoon at the track. You made sure that your car is ready, and off you go. You’ve gotten to the track and easily made it through tech. Finally, they call you to the staging lane and it’s your turn to impress the crowd with your car. But, during your pre-race burnout, everyone along the fence is pointing and laughing at your car as only one wheel churns out an obscene amount of smoke. You, my friend, need a limited-slip differential.

But, before you can actually understand why a limited-slip or locking differential is important in your performance car, we need to briefly talk about why your car needs any type of differential to begin with.

Keeping it basic, a differential is a device that compensates for the incurred differences in wheel speed. This difference in wheel speed naturally occurs during situations like when a car goes around a corner, or one tire loses traction.

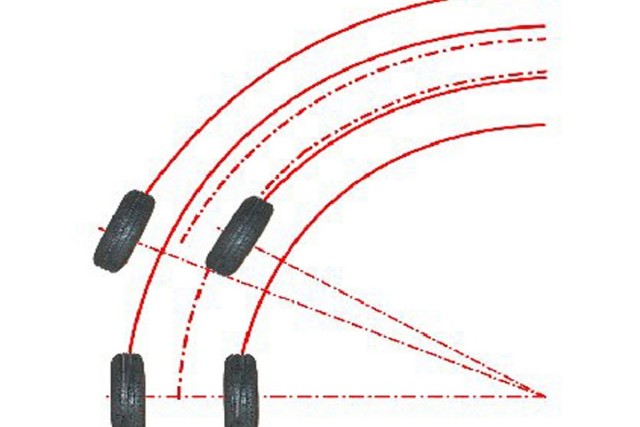

The inside and outside wheels of a car turn at different radii when cornering, so the tires need to rotate at different speeds

How They Work

When you enter into a corner with your car, there is a certain amount of tension that will build up in the differential. This happens because the outside wheel needs to rotate quicker than the inside wheel. The reason for this is due to the longer arc that it (the outside wheel) must travel. Without an open or limited-slip differential, eventually, this tension will relieve itself with either the outside wheel skipping/hopping over the surface, or worse yet, breakage — be it something in the rearend, or the drive shaft. This situation is obviously not a good one, hence our dive into understanding differentials.

Since differentials work by allowing a variable distribution of driving energy between the opposing wheels of an axle, consider a situation where one of your car’s tires is on a surface with good traction (asphalt), and the other tire is on a slippery/loose surface (gravel).

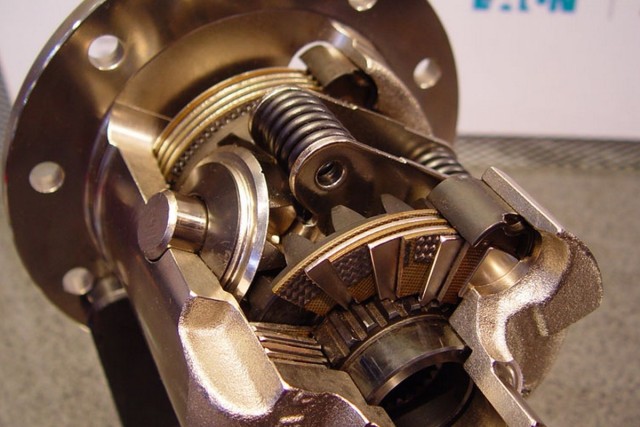

Eaton manufactured the factory Posi units for GM cars back in the day. They have clutch plates to link the drive axles.

When this occurs, a standard (open) differential will send the majority of power to the tire with the least resistance. In other words, your car ain’t moving.

Factory-style “open” differentials are just that, open. Their internal construction is devoid of any mechanism to contain this varying distribution of power, and the wheel with the least resistance is allowed to rotate — whether you want it to or not. In order to overcome this open-differential problem, limited-slip differentials were introduced. There are a variety of limited-slip differentials available to fit the rearend in your car, be it a 10-bolt or 12-bolt unit, you just need to decide what style is best for your situation.

In an attempt to help you with that research, With help from the folks at Eaton, we have compiled the following as a small, basic rundown of the different types of limited-slip differentials available, so you can decide which unit is best for you.

Clutch-Type Limited-Slip Differential

The clutch-type limited-slip differential is probably the most common version of the limited-slip differential. Many muscle cars had them installed from the factory, so this makes them a great choice for a stock-style rearend build.

A clutch-type limited-slip differential has the same components as an open differential, but it has the addition of a spring pack and a set of clutches. Many clutch-style differentials are also rebuildable.

Clutch-style limited-slip differentials have spring-loaded clutch packs. Although it takes a while, these clutch packs do wear.

How they work is, the spring pack pushes against the side gears, which in turn push on the clutches encased in the carrier. While under pressure, the side gears spin with the carrier when both wheels are moving at the same speed. During this situation, the clutches aren’t needed.

When this happens, the pressure that is applied by the clutches — and the resistance caused by the clutch’s friction material, fight to keep the wheels sync’d, ignoring the need for the difference in rotational speed.

Basically, the resistance created by the clutches makes both wheels rotate at the same speed. This means that in order for one wheel (outer) to rotate faster than the other, that wheel has to overpower the clutches, which it does, and this allows the outer wheel to spin faster. The pressure applied to the clutches is regulated by the stiffness of the springs, and these springs are changeable. Changing them allows for different pressures to be applied to the clutch system to suit certain driving habits.

Exploded view of the Auburn limited-slip differential shows the gears/cones that fit into the cone seat inside the housing.

Cone-Type Limited Slip Differentials

A cone-type differential uses friction that is produced not by clutch discs, but rather, by two cone-shaped axle gears that have a friction surface to engage both wheels and improve traction. In this type of rearend, the cone’s friction surface directly contacts the carrier case, and provides the friction needed to make the unit work.

The cones are made of a powdered-metal construction, and the metallurgical relationship between these two parts (cone and case) is very important so that they don’t gall when interacting. The cones in this differential are splined to the axle shafts and the axles rotate with the differential case.

There are coil springs positioned between both the right and left side gears that push the clutches into the differential case, thereby positioning the friction surface against a machined surface of the differential.

When rapid acceleration is experienced – or when one wheel loses traction – the differential’s spider/pinion gears that drive the cones push outward on the cone gears. This action increases friction between the cone surfaces and the differential case, reducing wheel spin. The major downfall to a cone-style differential is that it is not easily rebuildable. There are shops that have an exchange program, but, depending on your situation and location, that might not be a practical option.

Eaton’s Truetrac operates as a standard or open differential under normal driving conditions. When one wheel encounters a loss of traction, the gears engage and transfer torque to the wheel with traction.

Gear-Type Limited Slip Differential

In recent years, a third type of limited slip differential has been introduced. the Truetrac. This is a gear-driven limited slip that has been gaining in popularity. This helical-gear differential is different than a typical limited-slip differential in that it does not employ clutches or friction-surfaced cones. It works with three pairs of helical-cut pinion gears that revolve around the side gears that are connected to the axle via splines. There are three of these helical gears for each axle, and the unit works much like a traditional limited-slip differential by automatically transferring the available torque to the wheel with the most traction. But instead of the clutch or cone’s friction surface creating the torque bias, this occurs when the helical pinion gears are forced into the side gears. The greater the torque bias, the greater the wedging action, which improves traction.

The gear-driven differential is able to apply torque to both tires, but when cornering, biases most of the torque to the outside tire. This differential is virtually indestructible, and wear is almost non-existent.

These differentials — although physically different than a clutch or cone-style differential, are designed to directly replace an existing open or other limited-slip differential. Like a cone-style differential, these gear-driven units are not rebuildable.

We know that it happens, and you probably even know someone that does it, but while you or your buddy might think that a spool is the ultimate differential for street use, not only is it not recommended, it can be downright unsafe. When you’re driving in a straight line, there isn’t much of an issue, as both wheels are working together. But, throw a corner in there, and hang on. Remember at the beginning of the article we explained what a differential does? When both tires are locked together, both axles have to rotate at the same speed. When something wants to spin – regardless of the RPM – and it can’t, breakage is bound to occur. When using a spool, that breakage is usually an axle.

No Wrong Choice

Before choosing a differential, you need to evaluate the intended use of your ride. Your grocery-getter can survive with an open differential, but if occasional trips to the drag strip are planned, installing a clutch-type, or a torque-sensing unit should be considered. Hopefully, the insight that we have given you, will help you make an informed decision about the different differentials available, so you aren’t “that guy” at the starting line spewing smoke from one tire.