Back when we first picked up Project Lucky 13, the fifth-gen Camaro was in a pretty sad state. Missing everything from the engine and transmission to the brakes and wheels, we knew we had our work cut out for us.

But, when we looked at the mess that was our then-soon-to-be project car, all we could see was potential. After all, regardless of the fact that it was a theft-recovery vehicle, it was still a Camaro; carrying the spirit and legacy associated with that title, we felt that it deserved more than the junkyard.

Naturally then, that meant we would be attacking this build with a no-holds-barred approach. Keeping in line with the car’s heritage, Project Lucky 13 is destined for some serious track use. However, we also chose to include another facet by prescribing daily-driving duties. This presents the challenge of balancing the car’s practicality with its all-out performance, which calls for some seriously top-of-the-line hardware.

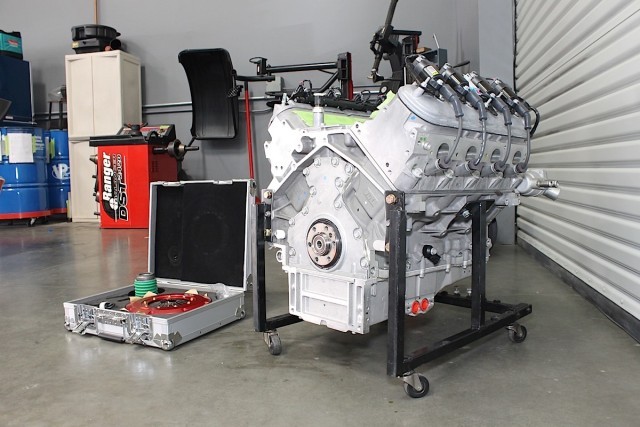

Up to this point, we’ve already tackled quite a few of the major things that our car needed (which, to be honest, was a lot). Thus far, we’ve gotten our seats and roll bar taken care of, a beefy Mantic clutch bolted up to our replacement crate engine, a road-hugging suspension base built out, and the bulletproof ZL1 driveline installed. After those came the install of a track-capable Be Cool cooling system, hardcore Wilwood Aerolite brake setup, and a set of sexy-yet-functional Forgeline wheels and road-hugging Toyo tires.

From left to right, Vogtland Coilovers, Wilwood Aerolite brakes, Mantic clutch attached to the LS7, and the Recaro seats, belts, and roll cage all installed on Lucky 13.

Despite all of this progress, none of the work we’ve yet done to Lucky 13 has entirely fallen in the “go fast” category. Of course, every bit of it was vital; we had to ensure our Camaro could handle all of the fun we want to have with it. However, finally–as we had been itching to do since day one–we were ready to plug in the Camaro’s new drivetrain.

Rethinking the Powerplant

Being an automatic SS model, the pony car previously stowed a variant of the venerable, 426-horsepower LS3 under its hood: the 400-horsepower L99. The differences in the L99 versus the LS3 are a 26-horsepower deficit, 0.3-lower compression ratio, 400-rpm-lower redline, and the addition of active fuel-management.

While the off-the-shelf LS3 is renowned for its broad, flat torque curve and power throughout the rev range, this means that it delivers power in somewhat of a one-size-fits-all fashion. Instead of giving most of its grunt in the first few thousand rpm, or offering exceptional mid-range torque, or even having loads of top end power, the LS3 is well-rounded. No doubt, it performs quite reasonably for the street, strip or track, but what if 426 (or in our case, 400) “well-rounded” ponies just isn’t enough? Enter the LS7.

While the LS3’s (and, by extension, L99’s) praises go on and on, we took this opportunity to reach beyond factory spec and give our future-track-warrior a bit more bite–51 cubic inches more bite, to be exact. Instead of opting for a 376-inch LS3, we chose to squeeze in the mighty 427-inch LS7. Thanks to Chevrolet Performance and its line of LS crate engines, getting our hands on a brand new mill was as easy as choosing it.

To the uninitiated, simply converting from the LS3 to the LS7 could seem a bit redundant. After all, the swap is both staying within the LS-family and sticking to natural aspiration; at a glance, the only discernible difference between the two mills is the eighth-liter gap in displacement.

However, make no mistake – not all LS’s are created equal. Despite sharing the same general architecture – with internals, heads, and even entire blocks often being shared between multiple power plants – the various LS engines (and their many derivatives, such as the Vortec series) can offer radically different characteristics.

Being the big kid on the block when it comes to LS-engine displacement, the LS7 called for some of the heaviest hardware in the General’s arsenal. As such, Chevy engineering packed the mill’s 4.125-inch-bore aluminum block with premium internals – like titanium connecting rods anchored with a forged steel crankshaft, CNC ported heads stuffed with lightweight titanium valves, and an LS7-specific camshaft yielding 0.591 inches of lift. The end result is an advertised 505 horsepower and 470 lb-ft of torque.

While this potent combination offers advantages like durability and high-efficiency right out of the gates, one of the major selling points of the LS7 is the fact that its power lives in the higher rev-range. This is largely thanks to the lightweight titanium components and standard dry sump oiling system.

Its hulking, 427-cubic-inch displacement make it no stranger to bottom-end torque and mid-range power, but – unlike with the LS3 – the high spinning that track duty demands is the rev-happy LS7’s bread and butter. This is the reason that Chevy chose it for its dedicated road-course maniac – the fifth-gen Z/28 – and likewise why we chose it for our own track warrior.

Being a car that will see a lifetime of track use (and being geared nice and tall to accommodate), our project-Camaro will often be spinning in the upper reaches of its capabilities – meaning that it will make great use of its new LS7.

Grabbing New Gears

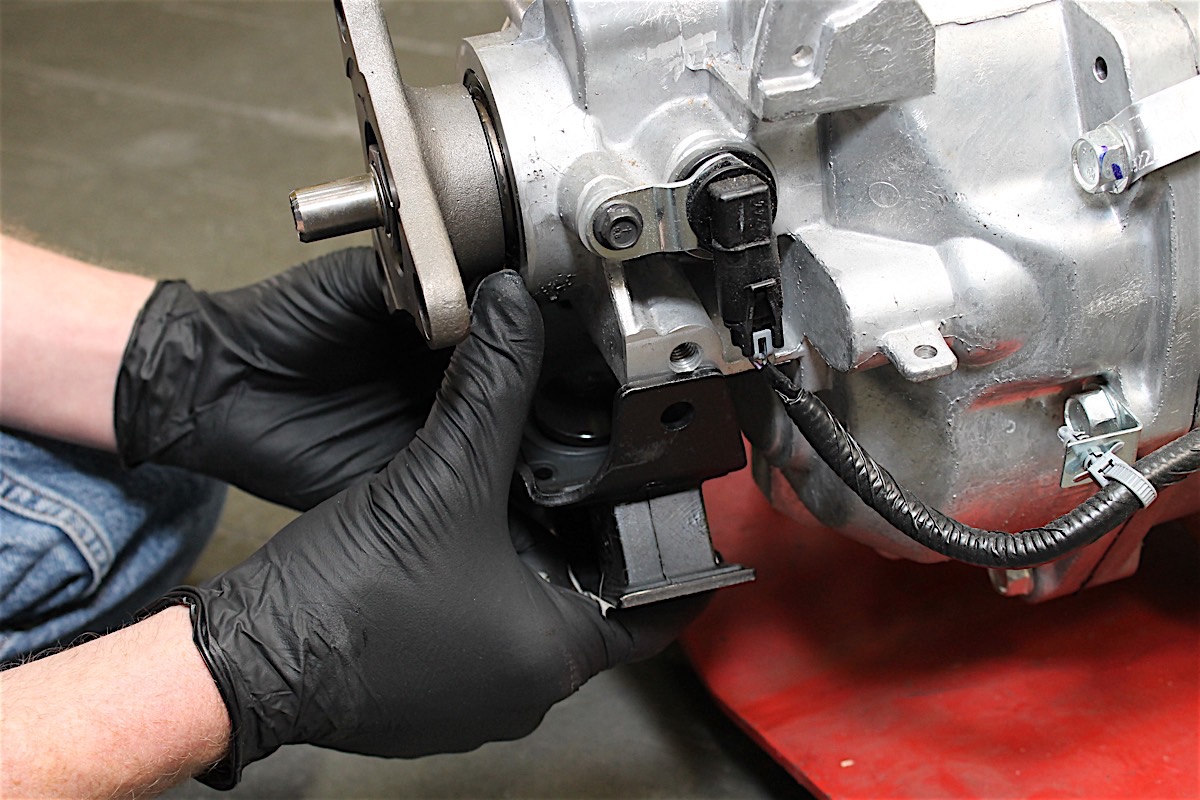

Backing up our well-chosen engine, of course, would have to be nothing other than a stout six-speed manual transmission. Filling this order for us is Tremec’s TR6060, which would take the place of the previously-employed Hydra-Matic 6L80 automatic transmission given by the factory.

Of the three main reasons we had for converting Lucky 13 to a manual gearbox, its intended application is, of course, the most obvious. Being a road racing machine, the TR6060 will allow us to keep the car in the best gear possible at all times and better make use of our LS7’s power.

The second reason for our upgrade to the TR6060 is durability. The 6L80 transmission previously in the car serves its purpose well for a mild, daily-driven street car, but has a safety rating of only a modest 439 pound-feet of input torque.

The TR6060, on the other hand, can handle a bit more abuse, transmitting up to a rated 650 pound-feet of input torque. When coupled with the Mantic cerametallic twin-disc clutch and the ZL1 driveshaft, rearend and half shafts we got from Chevrolet Performance, the gearbox and driveline will be more than capable of handling and delivering all of the power we plan to surge through it.

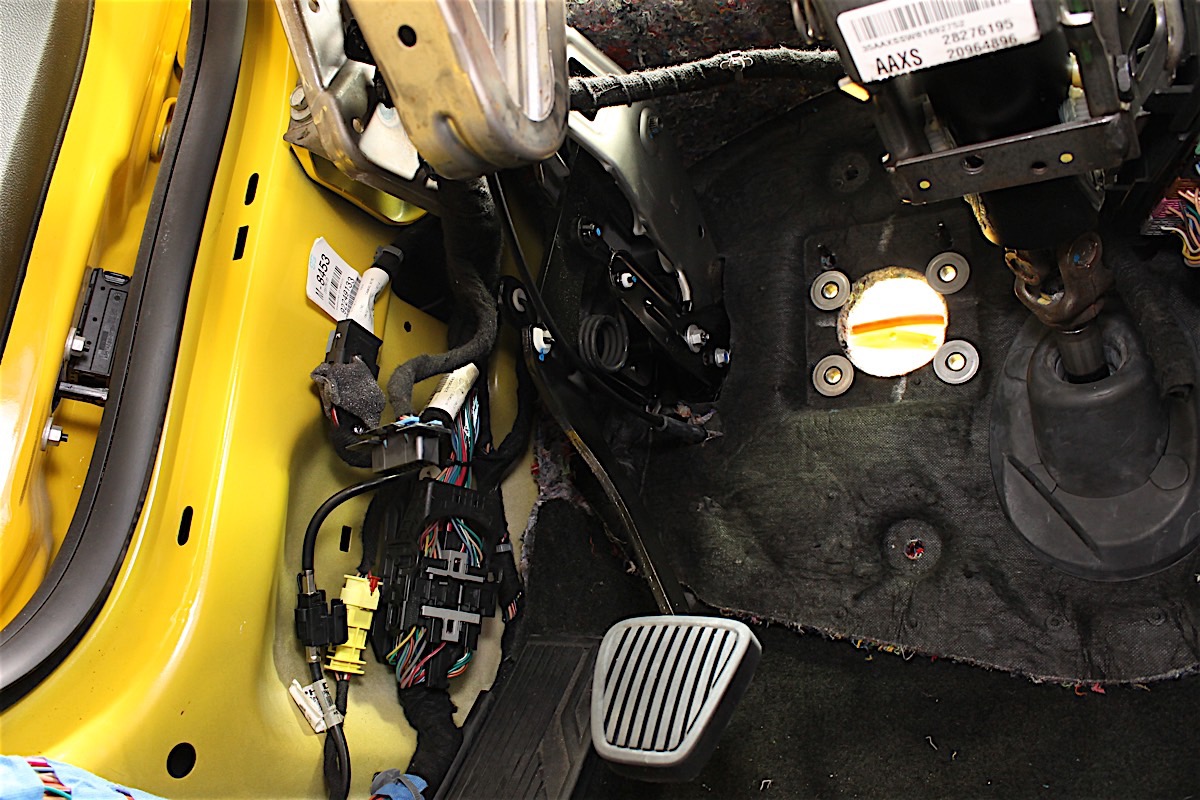

Out with the old, in with the new. The new six-speed shifter side-by-side with the old automatic gear selector we tore from Lucky 13’s carcass.

And – at the risk of offending some (most likely our drag racing audience) – we had a third reason for the TR6060 swap: automatic cars can be just plain boring to drive, especially around a road course. While the new, automatic-equipped sixth-gen Camaros at least have their paddle-shift feature to keep drivers busy, our fifth-gen never had such a luxury. It was only fitting that we upgrade from the original slush-box to something a bit more becoming of a true track car.

The Swap

For the swap itself, we obviously had quite the advantage since Lucky 13 had long been missing its drivetrain. But while getting to skip the removal procedures saved us a good chunk of time, we still had the challenges of undoing the thieves’ damage, converting the car to accept the LS7, and the physical installation ahead of us.

K&N 50-state legal intakes

After the LS7 was secure in its new home, we decided to purchase a factory LS3 airbox off eBay and called our friends at K&N Engineering for their 50-state legal FIPK cold air intake kit, pn 57-3074. We chose it for the following reasons:

- Retains 50 state OEM emissions compliance

- Frees up horsepower over the factory intake

- Retains all facotry connections

- Deletes factory silencers

But luckily for us, Pace Performance was able to provide an array of technical information, wiring diagrams, and valuable intelligence that helped us in overcoming these unforeseen issues.

Our first step in the swap was to take care of Lucky 13’s ECU. Pace supplied us with a new PCM (Powertrain Control Module) and PCM harness – which was pre-flashed for a manual-transmission-equipped 2013 Camaro SS – as well as TPS (Throttle Position Sensor) connector and TPS harness (as the LS7 connector is different). Our LS-tuning guru will be tuning the PCM to a factory LS7, emissions legal, tune.

With our Camaro’s brain-transplant taken care of, the heavy lifting could begin.

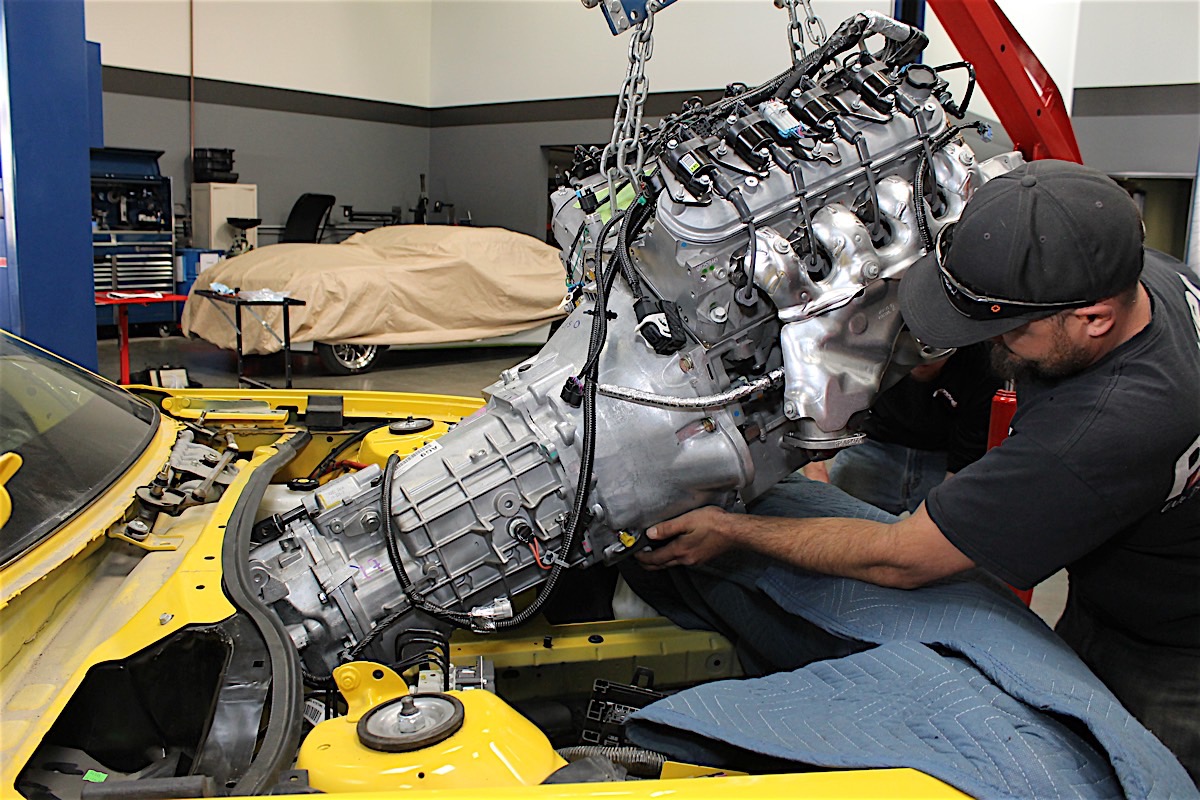

The Drop-In

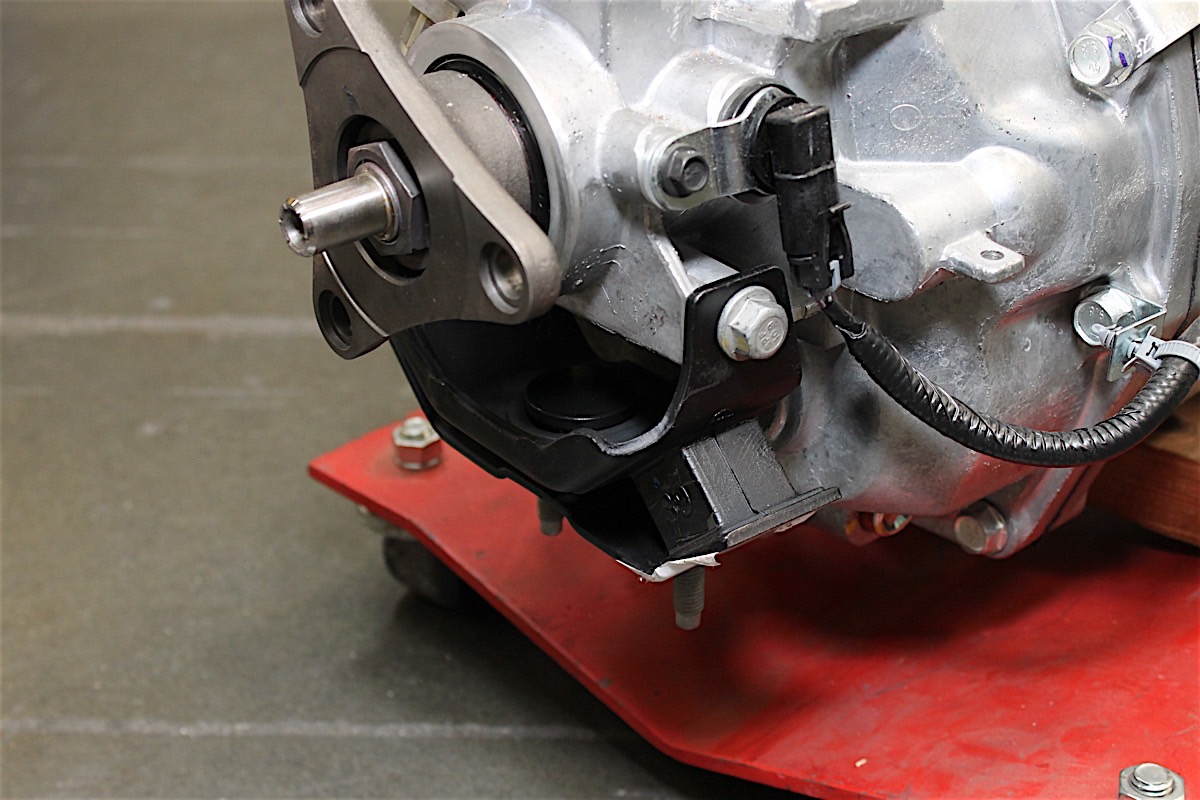

Being an LS-to-LS swap, we didn’t have too much to worry about when it came to shoehorning our new powerplant in. However, the block-side engine mounts that come with the crate-LS7 are Corvette-spec–meaning that they don’t quite pair up with the mounting locations in our Camaro. To remedy this, we purchased a set of Camaro-specific LS7 engine mounts, which allowed our new mill to painlessly seat between the front fenders.

The motor mounts bolt right on and allow the LS7 to easily slip between the fenders of our fifth-gen Camaro.

Getting our new TR6060 to settle in where the original 6L80 used to reside, on the other hand, took quite a bit more coercion. The engine-exchange was a reasonably straightforward procedure (thanks to the inherent unanimity of LS-engines), but the auto-to-manual conversion, however, is not for the faint of heart.

Not only did we need to replace our transmission wiring harness with a manual-spec harness (the alternative being the highly-tedious and easily-botched process of properly modifying our automatic-transmission harness), we got ourselves into a lot of work physically altering the car to receive the manual transmission.

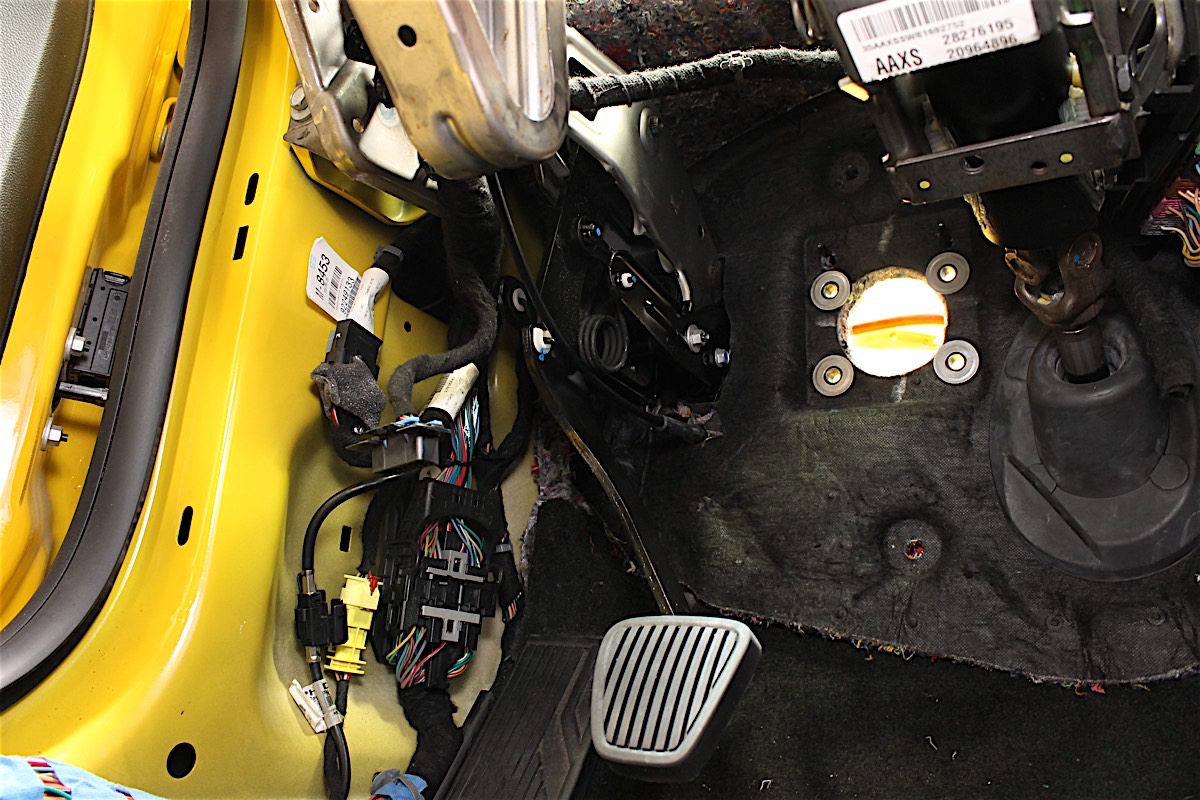

The entire pedal assembly seemed like it would be a breeze to swap, until we discovered just one bolt was hiding behind the dash, requiring us to pull the entire dashboard out of the car to get to it.

Physically installing the transmission was simple, thanks to our use of the proper transmission cross-member mount. However, in order to install and set up the clutch hydraulics and pedal, we needed to replace the brake booster mounting plate on the firewall, modify and route hosing from the brake booster itself, remove the entire dash structure, and perform a host of other alterations.

The trans crossmember and mounts bolted on in a snap. We wish we could say the same for the pedal assembly for the auto to manual conversion.

An auto-to-manual conversion isn’t something we recommend taking on with a nonchalant frame of mind. It is absolutely doable and the results are well worth it, but anyone tempted to dive into one will need to do all of their research, have the right tools and reference materials, and have the patience to see it through.

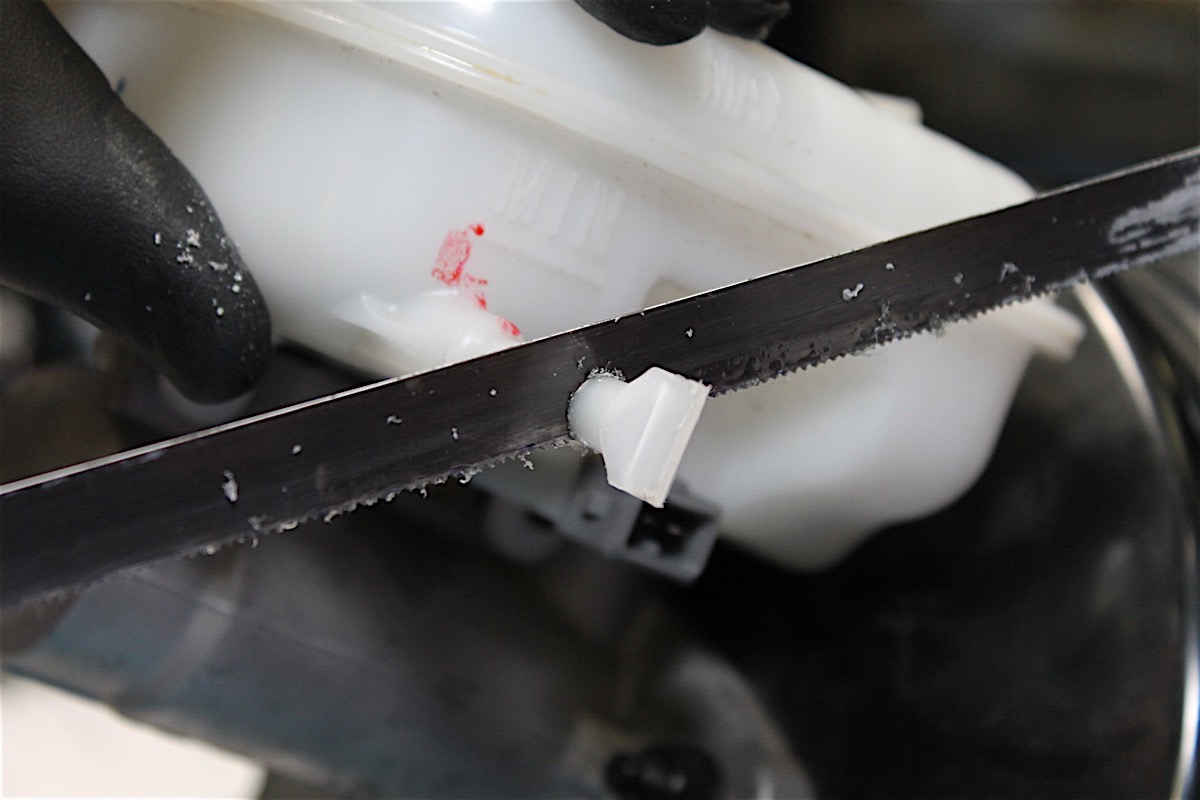

Swapping an auto to a manual requires a lot of work and a bit of cutting to make it all fit. We had to cut off what we would call a nipple on the brake reservoir, since the clutch and brakes share the one.

Our conversion on Lucky 13 is – as you can imagine – a story in and of itself. Stay tuned for the full auto-to-manual swap article coming in the near future.

Extra Exhalation

Before the powertrain was stuffed into its final resting place and successfully mated to the ZL1 driveline behind it, there were a few items needed to button up the LS7. We first looked to the exhaust manifolds.

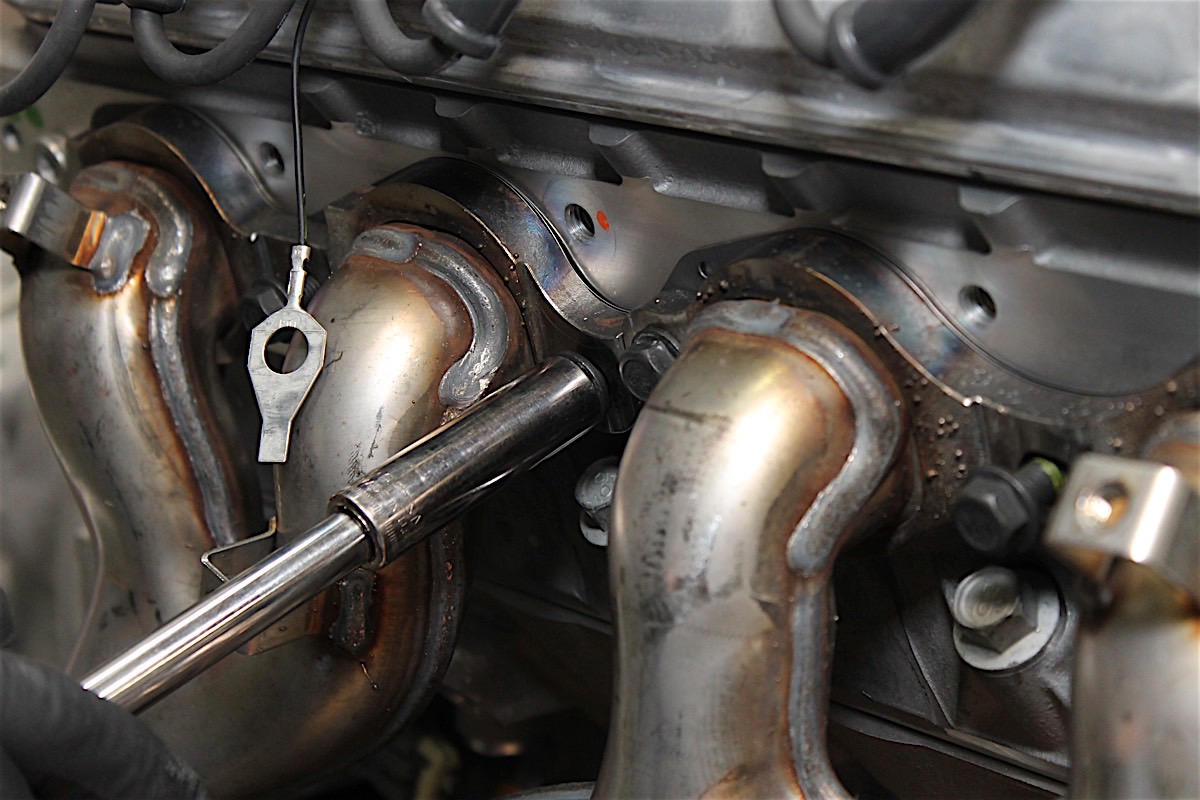

A side-by-side comparison of the LS7’s stock Corvette-style exhaust manifold (right) next to our Z/28 manifold (left). The Z/28 manifold uses a tubular design, although they are hard to distinguish when the lower heat shield is finally bolted on.

Out of the box, the LS7 is a very deep-breathing motor. Benefitting from CNC-ported heads, hefty 2.200-inch intake valves, silver-dollar-sized 1.610-inch exhaust valves, and a plump cam offering a balanced 0.591 inches of lift for both intake and exhaust, it’s capable of pumping incredible amounts of air.

While the factory crate-LS7 exhaust manifolds are well designed OE pieces, when it comes to emissions compliance and exhaust flow, they are Corvette spec, which simply weren’t designed with Camaro in mind. With fitment and performance being our primary concern, we were faced with two options: aftermarket headers or OE Z/28 manifolds. Since we original set out with the goal of retaining 50-state emissions compliance, we opted for the latter. However, the last thing we wanted was for any amount of flow and, consequently, power to be hindered by the bottlenecking of exhaust gasses (which, of course, standard exhaust manifolds are infamous for). In order to free up a bit more flow capacity, we ditched the engine’s standard Corvette manifolds for a set of the Z/28’s factory tri-Y headers, which we received from Chevrolet Performance.

The Z/28 manifolds are more along the lines of an OE header, engineered with a tri-Y design for maximum exhaust flow, and constructed of stainless steel for original equipment quality. Chevrolet Performance offers the Z/28 manifold package in their Camaro performance parts line-up under one, convenient part number. We do want to note, that when upgrading your SS Camaro, these manifolds will require Z/28 catalytic converters (not included).

Bolting the Z/28 manifold to the LS7 was a breeze with the engine out of the car and saved us a lot of headache when it comes to clearing the new motor mounts.

Yes, you read that right–we actually put catalytic converters on this car. One of the major goals of this project is to pass emissions here in the great state of California. We’re ensuring that all of the factory emissions equipment is installed and ready to blow clean so that we can register and drive this car on the road.

And with larger diameter tubing, a more conducive geometry, and even less restrictive cats, we’re certain that the Z/28 exhaust components will help offer performance that can overcome the detriment of any emissions equipment.

Quenching the Beast

With the drop-in and exhaust mounting out of the way, next on our list was fueling. Obviously, the 7.0-liter LS7 will demand more fuel than a 6.2-liter L99–especially with how we intend to use it.

While Lucky 13’s original L99 would have happily run off of 40 gallons of fuel per hour at 60 psi, we knew that our thirsty LS7 would be better off with a step-up in fuel delivery. It would only take mere moments of pushing our LS7 with a spread-thin fuel pump to result in a lean-run condition and detrimental engine damage, so an upgrade in fueling makes for some great insurance.

For the increase in go-juice, we looked to the Z/28’s more-muscular brother – the 580 horsepower ZL1. Rocking the 6.2-liter LSA, blown to 9 pounds of boost by its 1.9-liter Eaton supercharger, the ZL1 is quite familiar with high fuel-demands.

Its fuel pump – a returnless, pulse-width modulated unit like those in all modern LS fuel systems – delivers a healthy 54 gallons per hour at 65 psi. More than confident that it would be enough for Project Lucky 13, we reached out to Chevrolet Performance for the full ZL1 fuel pump kit.

The kit includes everything needed – the pump itself (with the integrated sender assembly), the tank seal, and comprehensive instructions. Installation was a simple drop in, requiring no extensive conversions or fuel tank alterations whatsoever. All we had to do was simply pull out the old pump and plug in the new one.

Stayin’ Lubed

The final task we had for buttoning up our Camaro’s new LS7 was setting up the dry sump system. Aside from the transmission conversion, this was arguably the most intensive part of the project – mainly due to the fact that the Camaro was not configured for a dry sump system from the factory.

The benefits, of course, are worth any amount of work to a true track machine. Compared to a wet sump, a dry sump system offers unparalleled oiling–most notably through hard corners, hard acceleration and sudden braking, where sloshing and oil starvation would normally occur. For such a large and high-revving engine like the LS7, the constant oil supply a dry sump system provides will offer the protection and performance it demands.

With these incentives in mind, we were eager to get everything plumbed. The LS7-crate engine does not come with the remote oil reservoir, fittings, or adapter that it requires, so we used this opportunity to reach out to Peterson Fluid Systems. From here we received our two-gallon oil tank, the accompanying breather can, and all the necessary mounting hardware, anodized fittings, and adapters. Perhaps one of the best features of the Peterson System is the ability to plumb the car with -AN lines and fittings.

We chose to mount Lucky 13’s oil tank in the same location the Z/28 has its own tank mounted, to save both time and space. The secondary oil cooler that our LS7 came with, however, was promptly removed and bypassed in favor of a higher-performance Derale Performance cooler mounted to the radiator. The secondary oil cooler, located just beside the oil pan, uses coolant to exchange heat from the oil. Not being the most capable setup, we knew our Camaro would benefit far more from an external air-to-liquid cooler, especially on a hot summer day at the road course.

While the dry-sump setup was fundamentally straightforward, it was still a rather tech-heavy portion of the swap. This being the case, we reserved all of the dirty details for its own story – stay tuned for the full in-depth oiling system article on how we tied together the Peterson dry sump and Derale cooler with Fragola Performance fittings coming in the near future.

The Bottom Line

All things said and done, we were able to pull off the swap without too many headaches. Moving from one LS engine to another, having the invaluable support of both Pace and Chevrolet Performance, and getting lucky that the thieves hadn’t caused too many roadblocks, the LS7-conversion was a relative piece of cake–at least for the techs in the Power Automedia garage, that is.

We’re incredibly excited at how beautifully Project Lucky 13 is coming along, especially considering the derelict state she started in. After the upcoming install of our Hooker BlackHeart cat-back exhaust –plus a little fine-tuning to acquaint the car with its new powerplant – our theft-recovery fifth-gen will back on the road like never before.

And in case you missed out on the installs leading up to this point, check out Lucky 13’s build thread to catch up on the whole story.