Pretty well any drag race car you look at today has a vacuum pump mounted to the engine, and the pumps are also becoming more common on street/strip cars. What does a vacuum pump do, you may wonder? It pumps vacuum, dummy! We brought in Greg Zucco from GZ Motorsports – one of the leading vacuum pump experts – to tell our readers how vacuum pumps work and how you can select the right one.

How Does a Vacuum Pump Work?

Every engine has a little bit of blow-by, which is combustion pressure that gets past the piston rings. Even newly rebuilt engines with standard rings, small ring gaps, and not a lot of cylinder pressure still have blow-by, but not much. However, build a race motor with 1.5mm rings and looser piston-to-wall clearances, and you’ll have quite a bit of air and fuel making its way past the rings and into the crankcase.

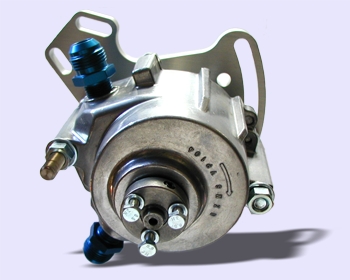

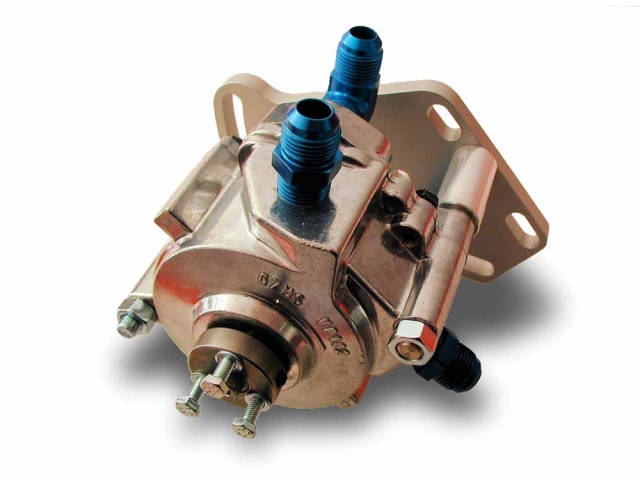

At left, this is GZ's true, bolt-on kit for LS-series engines. On the right, For more hardcore applications, DZ has this VP 104 Super Pro pump and and is rated at 33 cfm at 5,000 rpm and 21 inches hg at 1,900 rpm.

What’s the big deal with that? Well, it means less combustion chamber pressure and therefore less power potential; that pressurization of the crankcase makes it harder for the pistons to move down on the power stroke (known as pumping losses); it can cause oil leaks; and all that junk from the chambers also contaminates the oil. Plus, that air moving past the rings can contaminate the intake charge in many cases, and that will cost power. “The primary value of the vacuum is keeping oil from getting past and through the valve stem seals when the pressure in the engine is higher than the combustion chamber,” explains Zucco.

Zucco continued, “This reduces the ‘octane’ rating of the fuel. Along those same lines on the downward stroke with the intake valve open you get quite a bit of vacuum in the cylinder which will suck oil by the ring even more so than during the remainder of the cycle without compression. I believe that the work that the piston does going up and down probably makes no difference with vacuum or not because the same amount of pressure is acting on the bottom of the piston either direction it is going.”

How Vacuum Is Measured

The units for measuring vacuum is inches of mercury, which is recognized by the symbol “Hg”. Vacuum is measured as the differential between the ambient air pressure and the pressure inside the pump. Rather than output a negative Hg rating, pump makers display it as an absolute value of the differential between the two pressures.

A vacuum pump is therefore used to remove that crankcase pressure and create a negative-pressure (vacuum) condition in the crankcase. This allows the pistons to move more freely, the rings to seal better and reduce blow-by, and therefore the engine can make more power.

Typically, a vacuum pump is belt-driven and mounts to the front of the engine just like an alternator, and it pulls vacuum from the engine through one of the valve covers (which are naturally pressurized by the crankcase). A big hose connects the inlet (suction) side of the pump to the valve cover, and another hose on the pump is an outlet, sending the gases to a breather tank. The pump itself is a pretty simple device, though there are different schools of thought on pump construction.

GZ’ Take on Pumps

One of the most interesting designs is that offered by GZ Motorsports, which has a line of several different pumps for a variety of applications. Many pumps use a 3- or 4-vane system, where the vanes are flung outwards into the pump case by the centrifugal force of rotation, creating vacuum.

GZ’s pumps says they have improved this concept by adding carbon fiber vanes with Rulon wipers mounted to a crankshaft of sorts (which rides on bearings, just the engine’s crank), and the vanes never touch the case (the wipers do), so they can’t stick. These two design elements combine for very little friction, which makes the pump easier to spin and therefore frees up more engine horsepower. The GZ pumps also have internal manifold areas that allow air to come into the pump and collect, and then go out of the pump, something the other pumps don’t do.

The Right Pump

Whichever vacuum pump you decide to use, there are guidelines to picking the right one for your application. Since every engine is a little bit different, and there are just as many performance goals as there are engines, there is no one-size-fits-all pump.

Whichever vacuum pump you decide to use, there are guidelines to picking the right one for your application. Since every engine is a little bit different, and there are just as many performance goals as there are engines, there is no one-size-fits-all pump.

Vacuum pumps are rated by their ability to flow air, and the more air a pump will flow the more vacuum it will pull on the engine. In order for a pump to be effective, it must pull more vacuum than there is blow-by. Generally speaking, the smaller the engine the less blow-by. Of course, that all goes out the window on race engines—you can have a high-winding, turbocharged four-cylinder that generates more blow-by than a stock 454 big-block. For this reason, vacuum pump application charts usually dictate horsepower ratings instead of engine size.

A small pump that doesn’t pull enough vacuum can be made to act like a bigger pump by spinning it faster with a smaller pulley. Of course, vacuum pumps shouldn’t be spun faster than 5,000 or 6,000 rpm, so you can only go so far. Similarly, using too big of a pump for your engine may eliminate any power gains due to the power used to spin the pump. Just like with a supercharger, the more airflow the more horsepower required to turn the pump.

The vacuum of the pump while in use is measured with a gauge plumbed into the system, and should usually be kept to around 12 to 15 inches of Mercury. A vacuum control valve is used to prevent too much vacuum, like a bypass valve controls a blower’s boost level. Why limit the vacuum?

“Engine builders appear to believe that the lack of oil to wrist pins caused by removal of too much oil mist from the crankcase causes wrist pin damage,” explains Zucco. “Some engine builders report fluctuations in oil pressure above 12 inches, but we haven’t noticed that on engines we have observed during testing. However in a recent article, it was suggested that the air velocity passing through the block to heads at the oil return locations causes resistance to oil flowing back to the pan, which could indeed reduce oil pressure.”

Greg went on to say, “An air line from the fuel pump block off on a Chevrolet to the valve cover helps mitigate this problem, as well as possibly helping to balance the vacuum in the crankcase to that in the valve cover.”

One other thing to note about using a vacuum pump is that the engine must be completely sealed for the pump to be effective. If the pump is pulling outside air into the crankcase through leaky gaskets at the oil pan, intake manifold, distributor mount, valve covers, or anywhere else…well, you can see how that would affect it. With a used engine, you can check how well it’s sealed by pressurizing it with compressed air (not too much!) and listening for leaks.

Pump Sizing

Again, choose a vacuum pump based on horsepower output, not engine size. GZ’s recommendations using its products are as follows:

400-600 HP: VP101 or VP102 Sportsman pump run at 54% crankshaft speed. Larger small-blocks with a power adder might need to change to pulley to run at 64% crankshaft speed.

Racers the likes of NHRA and ADRL Pro Modified ace Mike Janis utilize GZ Motorsports vacuum pump products.

600-650 HP: For engines around the 600 hp range, we advise using a VP101 Sportsman pump running at 64% of crankshaft speed and a #12 inlet line. Pump speed will need to be increased to 75% in most cases for best results as your power levels near 750 HP for the VP101/VP102 pumps. The 75% pump speed should not be used for engines turning over 8,000 rpm to avoid over-speeding the pump. If it’s likely you’ll be making more power down the road, you might want to use the VP104 Super Pro pump with a single #10 intake line running at 54% of crank speed for a 750 HP Engine. This larger pump can be spun faster if needed, and you can increase the inlet line size to flow even more air. A #12 line is a good upgrade to get more air at lesser drag to the pump, however it is more expensive option.

750-1,000 HP: On the low end of this range we suggest using our VP104 Super Pro Pump with a single #10 intake line running at 54% of engine speed for optimum results. At the upper range of 900 hp, we recommend increasing the pulley ratio to 64% of crank speed and increasing the inlet line size to #12 to one valve cover, or two #10 lines to both valve covers.

1,000-2,000 HP: For large cubic inch engines with power adders the VP104 Super Pro Pump is needed at 64% on the lower HP end of this range to 75% of crank speed at approximately 1500 HP and above, we also recommend #12 inlet line to one valve cover, or #10 lines to two valve covers for maximum air flow.

Pump Size Versus Vacuum Generated

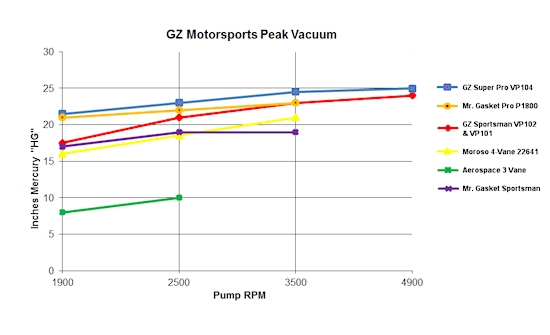

This is a comparison of various pumps’ peak vacuum, which is how much vacuum the pumps can pull when deadheaded.

The chart at right shows the net vacuum you can expect in a naturally aspirated motor with standard or low-tension rings and no vacuum control valve. These values assume the rings are in good shape (leak-down is not excessive) and there are no vacuum leaks in the engine. Note that net vacuum measured will tend to increase with RPM unless blow-by into the crankcase increases enough to reduce the negative net airflow out of the crankcase, thus reducing vacuum at higher RPM. It’s common to see the vacuum increase to a maximum and then reduce some at max RPM if the vacuum pump is not rated for enough airflow to maintain a net vacuum throughout the RPM range. Of course to achieve a constant net vacuum you need to have a vacuum control valve installed in order to let air into the engine when the maximum desired vacuum level is achieved.

As you can see, vacuum pumps are rather technical by nature, but once you have an understanding of what vacuum is and how to achieve the desired level of vacuum for your particular engine combination, you’ll be well on your way to making more horsepower, and that’s really what we all want, right? GZ Motorsports is one of the leading manufacturers of vacuum pumps, and if you’re undecided on what product you need for your engine, their helpful tech staff will be certain to get you on track.