The jury is still out whether using hydrogen as a fuel will save the planet. Some say it is a waste of energy because it takes more dirty fossil fuels to create, transport, and burn than if used more efficiently in other forms like a fuel cell. Despite the criticism, many in the automotive industry and elsewhere are not ready to give up on hydrogen as a replacement for gasoline to fuel internal combustion engines.

Mike Copeland of Arrington Performance and builder of the “Hydrogen Truck” that graced the floor at SEMA, says hydrogen offers the classic chicken or the egg problem. There’s no demand because there’s no infrastructure, and vice versa.

Top Gear echoed that sentiment, saying, “hydrogen production has lagged because there’s no demand, and demand has lagged because there’s no infrastructure, and infrastructure has lagged because there hasn’t been an uptick in either demand or supply.”

Copeland, Bosch (a major automotive supplier), and Shell, a giant energy company, want to change the paradigm of the most abundant element on the planet. No matter what part of the political spectrum, many believe that a future without fossil fuels is impossible without hydrogen playing a significant role. But to date, there’s been very little support for it because many proponents of electrification say that we need battery power first. But there are 90 million internal combustion vehicles on the roads in the U.S., and we need a way to save some of them — especially the classics.

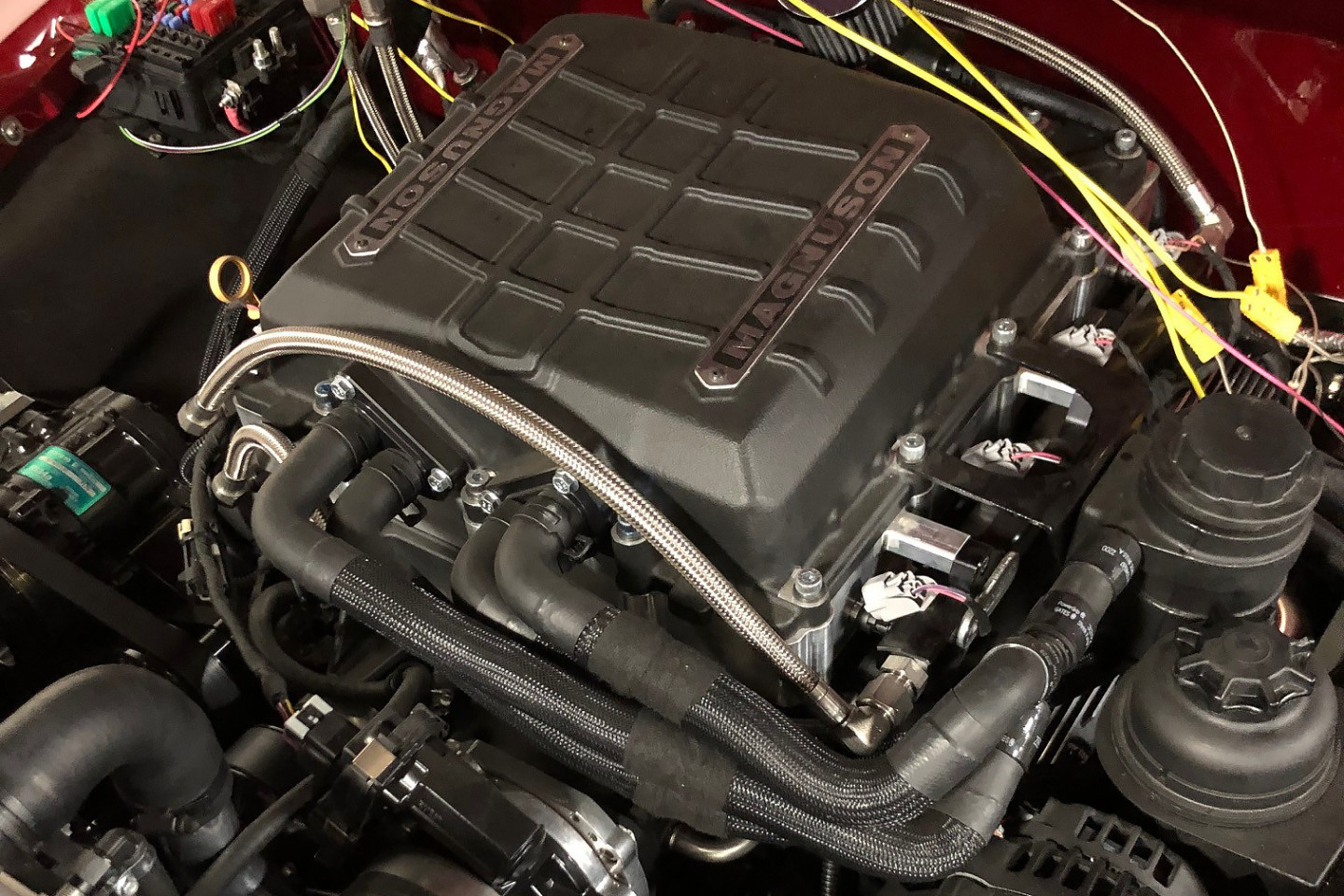

To that end, Copeland led a team that developed and built a hydrogen retrofit kit for his 1948 Chevy Truck aptly named “Zero.” The truck was put together by both Diversified Creations, who physically built the truck and adapted all the components into it, and Arrington Performance, who built the engine — a 6.2L supercharged LS motor. Arrington is responsible for all of the hydrogen work that goes behind it. But is hydrogen viable and safe?

We use the lower pressure threshold, 350 bar – roughly 5,074 psi. In fuel cell vehicles, they run at 700 bar, which is just over 10,000 psi. — Mike Copeland, Arrington Performance

Oh, The Humanity!

One of the questions that Copeland gets asked about is the safety of hydrogen. “Many people want to talk about the Hindenburg,” he says. “That’s the trigger in people’s minds when you talk about hydrogen. Is it explosive? Yes, it has that opportunity. We run a hydrogen tank in our truck that is DOT certified for crashes. So we eliminate a lot of those variables. But hydrogen is flammable, and we use it in a gaseous state. It is more dangerous in a liquid state.”

Hydrogen is commonly used at two pressure thresholds, says Copeland, who uses the lower pressure option. “We use the lower pressure threshold, 350 bar – roughly 5,074 psi. In fuel cell vehicles, they run at 700 bar, which is just over 10,000 psi. It increases the volume of hydrogen in the tank for a given size tank. So it basically doubles the range.” Some additional requirements make the higher pressure suboptimal for Copeland’s retrofit strategy.

Mike Copeland may be known as a Hemi guy, but he has plenty of experience with GM as well. He used a 6.2L supercharged LS as the base for the hydrogen conversion kit.

It is no secret that the automotive industry is leaning away (to put it mildly) from internal combustion. Jeff Smith recently wrote in Making Affordable Synthetic Fuels that GM has announced internally that they have stopped developing internal combustion engines. Nissan has made it more public. And Volvo was one of the first to announce its plans to stop producing internal combustion-powered vehicles globally by 2030 (GM set its target date for 2035). As hot-rodders, gearheads, and racers born with gasoline in our veins, this latest trend is disturbing and painful to hear.

Copeland is more resolute, however, because he may have a solution that will save millions of classic cars from the scrap pile. He plans to develop a retrofit kit that can be adapted to run on any internal combustion engine. It may be more expensive at first, but the prices should come down as the technology scales up. But first, there needs to be an infrastructure in many states to allow for hydrogen refueling. Right now, it is sparse.

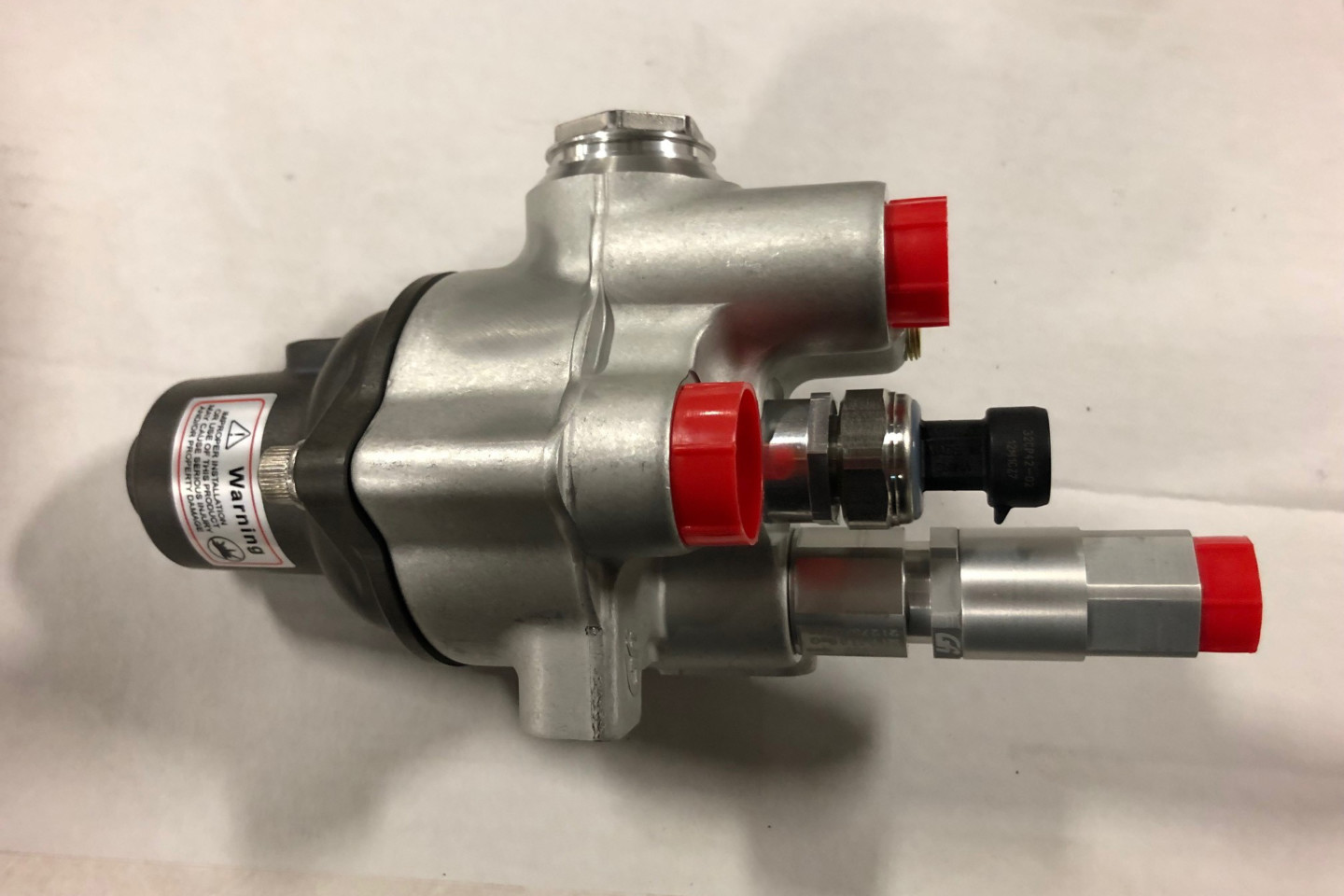

A custom fuel regulator was employed to handle the hydrogen gas, and it was not cheap for a one-off component, but Copeland hopes that the cost will come down once production scales up.

Grey, Blue, Green — The Colors of Hydrogen

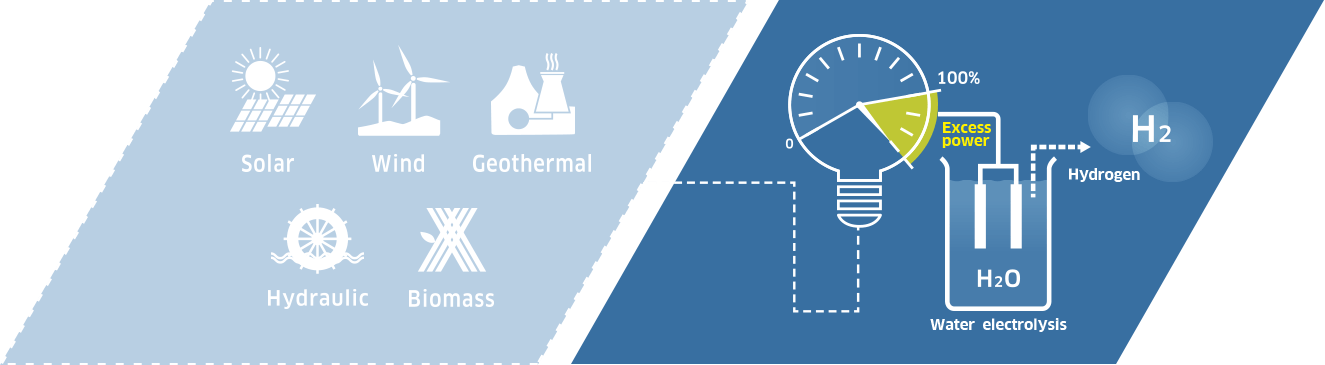

The terms Grey, Blue, and Green, are not questions on a cognitive test, it represents the three types of hydrogen that can be manufactured today. Hydrogen can be produced from various resources, including fossil fuels, nuclear energy, biomass, and renewable energy sources. This can be done via several processes. The gas it makes can be burned or used as a carrier to provide power. If it is generated using renewables, it can be a clean alternative to burning fossil fuels.

Green hydrogen is the ultimate landing point because it is produced with carbon-neutral energy sources such as solar or wind energy. Japan uses bio-sewage from a water treatment plant. But, there’s not enough development or demand to make it in large enough quantities for mass consumption.

“Green hydrogen is kind of in its infancy,” says Copeland. “There are several ways to produce it. Right now, there’s a facility in Michigan that manufactures blue hydrogen. They manufacture it on site. But they have limited availability as well.”

Blue hydrogen is made from methane byproducts or natural gas and is considered in the middle of a grey and green as far as the carbon it produces during the processing. Regardless, it takes a lot of energy to produce hydrogen, no matter how it is made. This is why critics say it would be better to use the energy in battery applications rather than add another step to refine it into a gaseous or liquid fuel.

“Fuel cell cars are still a ways off,” Copeland notes, “and it doesn’t address what we are supposed to do with our approximately 90 million ICE cars on the roads today, globally. And in the U.S. at least, we have a hotbed industry called the aftermarket that is based on hot-rodding cars with internal combustion engines.” But he says it doesn’t have to change if his plan comes to fruition, at least for the foreseeable future. And he has the ear of many people in Congress right now.

Copeland says that most states don’t have any hydrogen plants, but he notes that most states don’t have a reason to have them yet. “On the positive side, I’ve had several U.S. Senators reach out to me. I’ve been invited to speak in front of a group of 50 Senators to talk about hydrogen. Reactions have been excellent because they want to eliminate roadblocks to bring it to their states.”

Industry Savior Or Bust

Copeland is a lifelong gearhead and believes the best way to save the industry is by converting classic cars to hydrogen power. “It only takes one legislative act, and there will be no more internal combustion engines… I’ve always been one of those people that like to push technology. I like to do the things nobody’s ever done. I was in a meeting with people from Bosch, and they had a lot of interest. They’ve been doing some hydrogen work in Europe, so we agreed that they would support me with calibrations and some components if I would do the rest. And so my wife and I decided to spend the money and go do it.”

Tuning Hydrogen

You can’t just go out and buy an aftermarket ECU to run an engine on hydrogen. “The parameters are so far out of those bounds,” says Copeland. “The ranges are so different that we would be in trouble without the ability to write new code.”

Copeland explains that a typical gasoline engine runs at 14.7:1 stoichiometric air-fuel ratio, but hydrogen is a different animal. “We’ve been running from 75:1 to about 100:1 ratio.” That means there is almost zero timing advance. And the engine can run very lean without detonation.

Working with hydrogen is a challenge because it is one of the lightest elements on Earth and can leak out of standard fuel lines and fittings. All of the lines were upgraded to Mil-spec flexible lines that can hold the high pressures (around 5,000 psi).

It’s a very lean fuel. “We use hydrogen as a gas because in its liquid form, it requires some specific cooling and some other things to be safe,” explains Copeland. He can’t give away too many details because the plan is to develop this system used on the Zero Truck and then scale it for mass production so other builders can use it, too.

The fuel tank is essentially a modified welding tank. Most welding tanks are typically able to safely handle 2,000 psi. But going to 350 bar/5,000 psi requires some reinforcement and a custom regulator and fuel lines so that the fuel doesn’t leak out into the atmosphere. If you use a plastic fuel tank or a standard metal fuel tank, hydrogen will leak through it as well. Hydrogen is so light (and such a small molecule) that it will leak from fittings and junctions that are not perfectly sealed.

Copeland also uses specific injectors (two for each cylinder) and special O-rings throughout the entire system. Even the fuel lines are Mil-Spec and thicker than stainless-steel lines to keep the fuel from leaking. The goal is to get 500 horsepower from the supercharged LS engine. But Copeland says it won’t be difficult because hydrogen seems to react well to the Magnussen supercharger setup.

With the current price of gasoline skyrocketing, hydrogen is looking more competitive. Copeland says it works out to around $3.00 per gallon for blue hydrogen. But, as infrastructure is built and distribution increases, the cost could come down to about $1.50. Even Tony Stewart is a believer. He told someone Copeland knows at SEMA, “That truck just changed the world,” after seeing the project.

Copelands Zero Truck is a 1948 Chevy show stopper. Even without the hydrogen, it’s a beauty. But this one is fitted with a special fuel tank and fittings for the gaseous hydrogen fuel. It runs at 350 bar and can be filled in about three minutes at a station in Michigan.